| |

Distribution and Diet of Pacific Coast White Sharks

The White Shark's known range along the Pacific Coast of the United States

and Canada extends from Imperial Beach, San Diego County, California,

near the Mexican border, in the south, to the northwest Bering Sea

off the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, in the north. This range distribution

was determined from attacks, captures, strandings, and reliable observations.

White Shark attacks on humans have been authenticated from California,

Oregon and Washington. In addition to their attacks on humans, White

Sharks have also attacked boats and struck at, or bitten, numerous

other inanimate objects during the Twentieth Century. These incidents

were reported from California, Oregon, and Vancouver Island, British

Columbia, Canada. During the Twentieth Century, at least one observation,

stranding, or capture of a White Shark was reported from California,

Oregon, Washington, Vancouver Island, Alaska, and the Bering Sea.

Yakutat,

Alaska — Yakutat,

Alaska —

On Monday, September 6, 2004 charter boat captain Mark Sappington

was 14 miles offshore from Yakutat, Alaska, which is about 250 miles

north west of Sitka. He had six clients aboard his 30 ft halibut charter

fishing boat "Manifest Destiny." Sappington said

one of his "guys" had hooked a halibut and while

bringing the fish to the surface the line on the reel suddenly began

to "run out" as if something big had taken the

fish. He said, "It was obvious that the fish wasn't pulling

out the line."

When

the fish was finally reeled to the surface a large bite, at least

18 inches across, had been removed from the 60 lb halibut. The fishermen

quickly removed the halibut from the water as a large white shark

began to circle the boat. Sappington said, "It circled the

boat three times before it mouthed the swim step for several seconds.

After it let go of the swim step it circle the boat five more times.

It was definitely a great white about 20 feet in length."

The encounter left all on board breathless with a feeling of a once

in a lifetime experience. However, this might have been the second

time in as many days that Sappington had encountered this shark. On

Sunday, the day before, a charter member aboard Sappington's boat

had 400 pound test wire line stripped completely off of his reel at

an unbelievable speed. He believes it was the same shark. Sappington

said, "It was in the same place at the same time of day." When

the fish was finally reeled to the surface a large bite, at least

18 inches across, had been removed from the 60 lb halibut. The fishermen

quickly removed the halibut from the water as a large white shark

began to circle the boat. Sappington said, "It circled the

boat three times before it mouthed the swim step for several seconds.

After it let go of the swim step it circle the boat five more times.

It was definitely a great white about 20 feet in length."

The encounter left all on board breathless with a feeling of a once

in a lifetime experience. However, this might have been the second

time in as many days that Sappington had encountered this shark. On

Sunday, the day before, a charter member aboard Sappington's boat

had 400 pound test wire line stripped completely off of his reel at

an unbelievable speed. He believes it was the same shark. Sappington

said, "It was in the same place at the same time of day."

A

biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish & Game said this

was the fourth report of a large white shark in Southeast Alaska this

year. Historically, white sharks are no strangers to the coastal waters

of Alaska. In the summer of 1981 a salmon fisherman caught a white

shark off Yakutat that measured more than 18 feet in length. Authenticated

records of white shark captures and strandings date back to at least

1961 in the scientific literature. (Photographs courtesy of John Huppert) A

biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish & Game said this

was the fourth report of a large white shark in Southeast Alaska this

year. Historically, white sharks are no strangers to the coastal waters

of Alaska. In the summer of 1981 a salmon fisherman caught a white

shark off Yakutat that measured more than 18 feet in length. Authenticated

records of white shark captures and strandings date back to at least

1961 in the scientific literature. (Photographs courtesy of John Huppert)

Over the preceding four decades, captures or strandings of White

Sharks have provided valuable insights into their biology —

including dietary preferences. A brief description of a stranding

and a capture are presented below.

In

late September 1977 a local air taxi operator sighted a large shark

stranded on a beach 16 miles southwest of Ketchikan, Alaska. Fisheries

biologist Robert Larson examined the shark on 30 September 1977. The

adult male White Shark was 15 feet 4 inches in total length. Upon

dissection of the shark's stomach about 100 opaque circular objects

were discovered, each about 0.25 inches in diameter. John E. Fitch,

Research Director, California Department of Fish & Game, Long

Beach, subsequently identified them as lenses from fish eyes, most

probably salmonids. The number of lenses present in the shark's stomach

suggests that fish might provide a larger percentage of adult White

Shark nutritional requirements than previously thought. Although White

Sharks appear to prefer pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) as their main

staple after attaining maturity, they still consume fish. This fact

has been overtly omitted, or frequently understated, over the last

two or three decades by some White Shark researchers. The irrefutable

evidence from this stranding tells us that adult White Sharks are

apparently opportunistic predators and will readily take any prey

species that is available. In

late September 1977 a local air taxi operator sighted a large shark

stranded on a beach 16 miles southwest of Ketchikan, Alaska. Fisheries

biologist Robert Larson examined the shark on 30 September 1977. The

adult male White Shark was 15 feet 4 inches in total length. Upon

dissection of the shark's stomach about 100 opaque circular objects

were discovered, each about 0.25 inches in diameter. John E. Fitch,

Research Director, California Department of Fish & Game, Long

Beach, subsequently identified them as lenses from fish eyes, most

probably salmonids. The number of lenses present in the shark's stomach

suggests that fish might provide a larger percentage of adult White

Shark nutritional requirements than previously thought. Although White

Sharks appear to prefer pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) as their main

staple after attaining maturity, they still consume fish. This fact

has been overtly omitted, or frequently understated, over the last

two or three decades by some White Shark researchers. The irrefutable

evidence from this stranding tells us that adult White Sharks are

apparently opportunistic predators and will readily take any prey

species that is available.

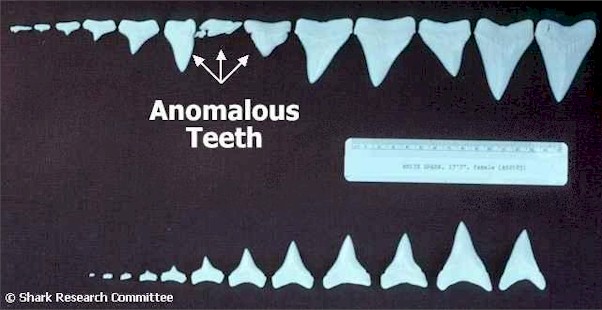

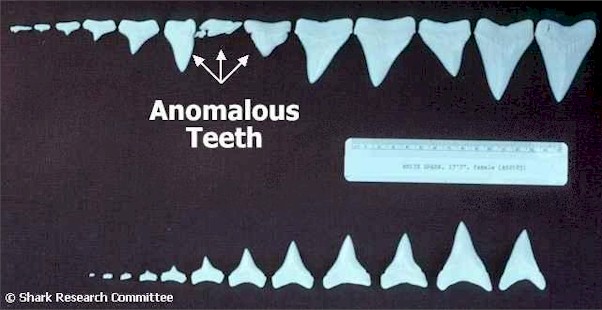

Commercial

fisherman Joe Friscia captured an adult female White Shark in his

drift gill net on 18 September 1985, about 15 miles southwest of Point

Vicente, Los Angeles County, California. The shark was 17 feet 7 inches

in length and weighed 4,140 pounds. The accuracy of the shark's weight

is indisputable. The 'truck scale' used to weigh the shark was checked

by the California Department of Weights and Measures and found to

be accurate to within ± 5 pounds. When the shark's stomach was dissected

it was found to contain the remnants of two pinnipeds — an adult

Harbor Seal (Phoca vitulina) and a 'roto tagged' juvenile Elephant

Seal (Mirounga angustirostris). Examination of the shark's

jaws revealed three individual rows of upper lateral teeth to be anomalous.

Upon closer scrutiny, over a dozen stingers of Bat Rays (Myliobatus

californicus) were found imbedded in the shark's upper and lower

jaws. Several of these stingers had penetrated tooth germ sites (the

area of the jaw where tooth formation occurs), causing permanent damage

to these three individual teeth. Several of the stinger wounds were

recent, suggesting that this shark had fed not only on pinnipeds but

also on benthic (bottom-dwelling) Bat Rays (Photograph courtesy Gordon

Hubbell). Commercial

fisherman Joe Friscia captured an adult female White Shark in his

drift gill net on 18 September 1985, about 15 miles southwest of Point

Vicente, Los Angeles County, California. The shark was 17 feet 7 inches

in length and weighed 4,140 pounds. The accuracy of the shark's weight

is indisputable. The 'truck scale' used to weigh the shark was checked

by the California Department of Weights and Measures and found to

be accurate to within ± 5 pounds. When the shark's stomach was dissected

it was found to contain the remnants of two pinnipeds — an adult

Harbor Seal (Phoca vitulina) and a 'roto tagged' juvenile Elephant

Seal (Mirounga angustirostris). Examination of the shark's

jaws revealed three individual rows of upper lateral teeth to be anomalous.

Upon closer scrutiny, over a dozen stingers of Bat Rays (Myliobatus

californicus) were found imbedded in the shark's upper and lower

jaws. Several of these stingers had penetrated tooth germ sites (the

area of the jaw where tooth formation occurs), causing permanent damage

to these three individual teeth. Several of the stinger wounds were

recent, suggesting that this shark had fed not only on pinnipeds but

also on benthic (bottom-dwelling) Bat Rays (Photograph courtesy Gordon

Hubbell).

During the Twentieth Century there were many references to fish, and

even crustaceans, being found in the digestive tracts of adult White

Sharks that were captured off the Pacific Coast. The variety and number

of marine mammals, fishes and crustaceans reported from these specimens

suggests that the only preference adult White Sharks might have when

actively hunting is the availability of the prey, rather than its

species.

Dietary Stages and Carrion Feeding

Research of the adult White Shark’s predatory behavior has

yielded some intriguing data, in addition to some exciting film footage.

The sight of a three or four thousand pound shark leaping vertically

out of the water, in a ‘Polaris Attack’ on a marine mammal,

sends chills through our collective psyches. Then again juvenile White

Sharks are incapable of capturing adult marine mammals and must employ

other strategies to feed on smaller prey. The variety of predatory

strategies and prey in the White Shark diet has lead to much speculation

about ‘shifts’ from one form of feeding to another. To

clarify these dietary stages a brief discussion would seem appropriate.

The following is what is currently known about the diet of the White

Shark from juvenile to adult, followed by a description of a form

of feeding not usually discussed in the literature.

The dietary stages, and/or preferences, of the White Shark throughout

its life are a function of two components — availability and

capability. Simply put, a White Shark will pursue any prey species

that is readily available and that the shark is capable of capturing.

A juvenile White Shark is not capable of capturing marine mammals

so its diet consists of fishes and invertebrates. Conversely, an adult

White Shark is capable of capturing adult marine mammals, especially

the Elephant Seal (Mirounga angustirostris), therefore they

are a primary prey species in the sharks diet.

In 1962 the Shark Research Committee began a research project to

determine the causal species and motivations for shark/human interactions

along the Pacific Coast of North America. This project continues to

this day. A by-product of this research was the field and laboratory

studies that were conducted on dozens of juvenile and adult White

Sharks. It was determined by the middle 1970s that juvenile White

Sharks were ‘pupped’ in the early spring, close inshore,

from Pt. Conception, Santa Barbara south to the Mexican border. This

specific region of coastline provided the habitat necessary for the

newborns survival. Examination of juvenile White Shark stomach contents

revealed numerous species of invertebrates and benthic sharks, rays,

and teleost fishes. One prey species in particular was frequently

found in the stomachs that were examined — the California Grunion

(Leuresthes tenuis) (see

grunion).

As newborns and yearlings, White Shark energy reserves, which are

concentrated in their livers, are minimal at best so it is necessary

that they begin to feed almost immediately. It is not surprising that

juvenile White Sharks are frequently observed close inshore off Southern

California beaches from April to September, the same months coincidentally

that the Grunion spawns occur. Millions of egg-laden Grunion provides

a bountiful supply of protein twice monthly for the young White Shark,

a necessity for the newborn sharks if they are to survive their first

year of life. In addition to Grunion, the young sharks also feed on

other fishes that are attracted to these spawns.

At

a length of 2 to 3 meters the White Shark’s diet expands to

include pelagic fishes, such as tunas and mackerels. After attaining

a length of 3 meters, the sub-adult White Shark is now capable of

capturing marine mammal prey, like Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina)

and California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus). Photograph

of the Harbor Seal taken at the Children's Pool, La Jolla in 2005

courtsey of Debbie Beacham. This is also when the shark starts employing

‘Polaris Attacks’ when hunting their marine mammal prey.

It is believed that this type of hunting strategy either disables

or kills the prey on impact, thereby reducing the likelihood of injury

to the shark from the struggling pinniped. Larger marine mammals,

such as the Elephant Seal, seem to be a favored prey of White Sharks

over 4 meters in length. The size of both predator and prey would

seem to be the determining factor in this dietary stage. However,

this does not mean that adult White Sharks consume only marine mammals.

As noted in previous examples, pelagic and benthic fishes and crustaceans

remain an import source of energy in the adult White Shark diet. At

a length of 2 to 3 meters the White Shark’s diet expands to

include pelagic fishes, such as tunas and mackerels. After attaining

a length of 3 meters, the sub-adult White Shark is now capable of

capturing marine mammal prey, like Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina)

and California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus). Photograph

of the Harbor Seal taken at the Children's Pool, La Jolla in 2005

courtsey of Debbie Beacham. This is also when the shark starts employing

‘Polaris Attacks’ when hunting their marine mammal prey.

It is believed that this type of hunting strategy either disables

or kills the prey on impact, thereby reducing the likelihood of injury

to the shark from the struggling pinniped. Larger marine mammals,

such as the Elephant Seal, seem to be a favored prey of White Sharks

over 4 meters in length. The size of both predator and prey would

seem to be the determining factor in this dietary stage. However,

this does not mean that adult White Sharks consume only marine mammals.

As noted in previous examples, pelagic and benthic fishes and crustaceans

remain an import source of energy in the adult White Shark diet.

These three dietary stages all require the hunting and capturing

of the prey in question, whether invertebrate, fish, or pinniped.

A more efficient method of obtaining food, in terms of energy conservation,

is carrion feeding, although it would be difficult to even hazard

a guess as to what percentage of an adult White Shark's energy requirements

are provided by this type of feeding. Generally, the carcasses involved

in this form of feeding are whales, which have been shown to have

energy-rich blubber. This is a very efficient method for the adult

White Shark to obtain its energy requirements. The shark expends a

minimum amount of energy to obtain a maximum amount of high-caloric,

energy-rich blubber. These feeding events are frequently observed

by fishermen aboard sport and/or commercial fishing vessels. The following

is an example of a carrion-feeding White Shark.

| On 10 September 1989, Tony DiCristo and his fishing

companion, Dan Fink, were aboard the Velmar, DiCristo's 11.6-meter

fiberglass boat, gently drifting about 10 kilometers off Palos

Verdes Estates, Los Angeles County, California (33°46.0' N;

118°20.0' W). They were taking turns filming a 4-to-5-meter

White Shark that was feeding on the carcass of a whale. The current

had slowly carried the boat close to the carcass of the whale

— tentatively identified as a Humpback Whale (Megaptera

novaeangliae) — when the shark abruptly abandoned its

feeding, turned and swam over to the Velmar, and bit the swim

step several times. The shark caused only minimal damage to the

step, but its actions shocked both fishermen. The shark then sounded

and was not observed for several minutes. However, after DiCristo

moved the boat 10 to 15 meters from the whale the shark returned

to feed. Within several minutes the boat had again drifted to

within 3 to 5 meters of the whale, whereupon the shark suddenly

turned and, moving swiftly, rammed the boat several times, pushing

it several meters across the surface. These startling events took

place over a four-to-five-hour period. Both fishermen described

the shark's actions as being more combative than predatory, almost

like it was attempting to "frighten or chase us away,

rather than eat the boat." Whenever the boat would drift

near the whale, the shark would abandon the carcass and focus

its attention on the boat. |

|

|

|

|

Yakutat,

Alaska —

Yakutat,

Alaska —  When

the fish was finally reeled to the surface a large bite, at least

18 inches across, had been removed from the 60 lb halibut. The fishermen

quickly removed the halibut from the water as a large white shark

began to circle the boat. Sappington said, "It circled the

boat three times before it mouthed the swim step for several seconds.

After it let go of the swim step it circle the boat five more times.

It was definitely a great white about 20 feet in length."

The encounter left all on board breathless with a feeling of a once

in a lifetime experience. However, this might have been the second

time in as many days that Sappington had encountered this shark. On

Sunday, the day before, a charter member aboard Sappington's boat

had 400 pound test wire line stripped completely off of his reel at

an unbelievable speed. He believes it was the same shark. Sappington

said, "It was in the same place at the same time of day."

When

the fish was finally reeled to the surface a large bite, at least

18 inches across, had been removed from the 60 lb halibut. The fishermen

quickly removed the halibut from the water as a large white shark

began to circle the boat. Sappington said, "It circled the

boat three times before it mouthed the swim step for several seconds.

After it let go of the swim step it circle the boat five more times.

It was definitely a great white about 20 feet in length."

The encounter left all on board breathless with a feeling of a once

in a lifetime experience. However, this might have been the second

time in as many days that Sappington had encountered this shark. On

Sunday, the day before, a charter member aboard Sappington's boat

had 400 pound test wire line stripped completely off of his reel at

an unbelievable speed. He believes it was the same shark. Sappington

said, "It was in the same place at the same time of day."

A

biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish & Game said this

was the fourth report of a large white shark in Southeast Alaska this

year. Historically, white sharks are no strangers to the coastal waters

of Alaska. In the summer of 1981 a salmon fisherman caught a white

shark off Yakutat that measured more than 18 feet in length. Authenticated

records of white shark captures and strandings date back to at least

1961 in the scientific literature. (Photographs courtesy of John Huppert)

A

biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish & Game said this

was the fourth report of a large white shark in Southeast Alaska this

year. Historically, white sharks are no strangers to the coastal waters

of Alaska. In the summer of 1981 a salmon fisherman caught a white

shark off Yakutat that measured more than 18 feet in length. Authenticated

records of white shark captures and strandings date back to at least

1961 in the scientific literature. (Photographs courtesy of John Huppert) In

late September 1977 a local air taxi operator sighted a large shark

stranded on a beach 16 miles southwest of Ketchikan, Alaska. Fisheries

biologist Robert Larson examined the shark on 30 September 1977. The

adult male White Shark was 15 feet 4 inches in total length. Upon

dissection of the shark's stomach about 100 opaque circular objects

were discovered, each about 0.25 inches in diameter. John E. Fitch,

Research Director, California Department of Fish & Game, Long

Beach, subsequently identified them as lenses from fish eyes, most

probably salmonids. The number of lenses present in the shark's stomach

suggests that fish might provide a larger percentage of adult White

Shark nutritional requirements than previously thought. Although White

Sharks appear to prefer pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) as their main

staple after attaining maturity, they still consume fish. This fact

has been overtly omitted, or frequently understated, over the last

two or three decades by some White Shark researchers. The irrefutable

evidence from this stranding tells us that adult White Sharks are

apparently opportunistic predators and will readily take any prey

species that is available.

In

late September 1977 a local air taxi operator sighted a large shark

stranded on a beach 16 miles southwest of Ketchikan, Alaska. Fisheries

biologist Robert Larson examined the shark on 30 September 1977. The

adult male White Shark was 15 feet 4 inches in total length. Upon

dissection of the shark's stomach about 100 opaque circular objects

were discovered, each about 0.25 inches in diameter. John E. Fitch,

Research Director, California Department of Fish & Game, Long

Beach, subsequently identified them as lenses from fish eyes, most

probably salmonids. The number of lenses present in the shark's stomach

suggests that fish might provide a larger percentage of adult White

Shark nutritional requirements than previously thought. Although White

Sharks appear to prefer pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) as their main

staple after attaining maturity, they still consume fish. This fact

has been overtly omitted, or frequently understated, over the last

two or three decades by some White Shark researchers. The irrefutable

evidence from this stranding tells us that adult White Sharks are

apparently opportunistic predators and will readily take any prey

species that is available. Commercial

fisherman Joe Friscia captured an adult female White Shark in his

drift gill net on 18 September 1985, about 15 miles southwest of Point

Vicente, Los Angeles County, California. The shark was 17 feet 7 inches

in length and weighed 4,140 pounds. The accuracy of the shark's weight

is indisputable. The 'truck scale' used to weigh the shark was checked

by the California Department of Weights and Measures and found to

be accurate to within ± 5 pounds. When the shark's stomach was dissected

it was found to contain the remnants of two pinnipeds — an adult

Harbor Seal (Phoca vitulina) and a 'roto tagged' juvenile Elephant

Seal (Mirounga angustirostris). Examination of the shark's

jaws revealed three individual rows of upper lateral teeth to be anomalous.

Upon closer scrutiny, over a dozen stingers of Bat Rays (Myliobatus

californicus) were found imbedded in the shark's upper and lower

jaws. Several of these stingers had penetrated tooth germ sites (the

area of the jaw where tooth formation occurs), causing permanent damage

to these three individual teeth. Several of the stinger wounds were

recent, suggesting that this shark had fed not only on pinnipeds but

also on benthic (bottom-dwelling) Bat Rays (Photograph courtesy Gordon

Hubbell).

Commercial

fisherman Joe Friscia captured an adult female White Shark in his

drift gill net on 18 September 1985, about 15 miles southwest of Point

Vicente, Los Angeles County, California. The shark was 17 feet 7 inches

in length and weighed 4,140 pounds. The accuracy of the shark's weight

is indisputable. The 'truck scale' used to weigh the shark was checked

by the California Department of Weights and Measures and found to

be accurate to within ± 5 pounds. When the shark's stomach was dissected

it was found to contain the remnants of two pinnipeds — an adult

Harbor Seal (Phoca vitulina) and a 'roto tagged' juvenile Elephant

Seal (Mirounga angustirostris). Examination of the shark's

jaws revealed three individual rows of upper lateral teeth to be anomalous.

Upon closer scrutiny, over a dozen stingers of Bat Rays (Myliobatus

californicus) were found imbedded in the shark's upper and lower

jaws. Several of these stingers had penetrated tooth germ sites (the

area of the jaw where tooth formation occurs), causing permanent damage

to these three individual teeth. Several of the stinger wounds were

recent, suggesting that this shark had fed not only on pinnipeds but

also on benthic (bottom-dwelling) Bat Rays (Photograph courtesy Gordon

Hubbell).

At

a length of 2 to 3 meters the White Shark’s diet expands to

include pelagic fishes, such as tunas and mackerels. After attaining

a length of 3 meters, the sub-adult White Shark is now capable of

capturing marine mammal prey, like Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina)

and California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus). Photograph

of the Harbor Seal taken at the Children's Pool, La Jolla in 2005

courtsey of Debbie Beacham. This is also when the shark starts employing

‘Polaris Attacks’ when hunting their marine mammal prey.

It is believed that this type of hunting strategy either disables

or kills the prey on impact, thereby reducing the likelihood of injury

to the shark from the struggling pinniped. Larger marine mammals,

such as the Elephant Seal, seem to be a favored prey of White Sharks

over 4 meters in length. The size of both predator and prey would

seem to be the determining factor in this dietary stage. However,

this does not mean that adult White Sharks consume only marine mammals.

As noted in previous examples, pelagic and benthic fishes and crustaceans

remain an import source of energy in the adult White Shark diet.

At

a length of 2 to 3 meters the White Shark’s diet expands to

include pelagic fishes, such as tunas and mackerels. After attaining

a length of 3 meters, the sub-adult White Shark is now capable of

capturing marine mammal prey, like Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina)

and California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus). Photograph

of the Harbor Seal taken at the Children's Pool, La Jolla in 2005

courtsey of Debbie Beacham. This is also when the shark starts employing

‘Polaris Attacks’ when hunting their marine mammal prey.

It is believed that this type of hunting strategy either disables

or kills the prey on impact, thereby reducing the likelihood of injury

to the shark from the struggling pinniped. Larger marine mammals,

such as the Elephant Seal, seem to be a favored prey of White Sharks

over 4 meters in length. The size of both predator and prey would

seem to be the determining factor in this dietary stage. However,

this does not mean that adult White Sharks consume only marine mammals.

As noted in previous examples, pelagic and benthic fishes and crustaceans

remain an import source of energy in the adult White Shark diet.