|

|

Unprovoked White Shark Attacks on DiversDuring the Twentieth Century divers constituted the largest number of victims for any of the four victim groups: divers, surfers, swimmers, and kayakers. There were 108 authenticated unprovoked shark attacks reported from the Pacific Coast of North America, with 50 (46%) directed at divers. The White Shark was determined to be the species responsible in 45 (90%) of the 50 recorded attacks on divers.

The sky was overcast and the sea calm. The attack took place at 0830 hrs off Pigeon Point, between Half Moon Bay and Santa Cruz, California (37° 11.6'N; 122°24.5'W). Conger and his dive companion, Chris Rehm, were 0.4 km north of Pigeon Point. Conger was dressed in a black wetsuit and shared with Rehm a blue-and-yellow surf mat. They were 150 m from shore, in 2 fm of water with less than 1 m of visibility. Conger and Rehm had been in the water 20 to 30 minutes and had collected two or three abalone. The ocean floor was rocky and reef-like, with short kelps and sea grasses covering the majority of the substrate. The divers were 5 m apart, with Conger resting vertically in the water looking out to sea, toward the west. Rehm was holding onto the mat, facing north and watching his friend, when to his unbelieving eyes a “huge White Shark came up, grabbed him [Conger] from behind, and while shaking him violently, pulled him under the water. I never saw the shark before the attack,” Rehm told researchers Lea and Collier. Within a few seconds the shark reappeared with its back completely out of the water, with Conger still in its mouth. Almost immediately upon surfacing, “like a big submarine,” the shark headed toward Rehm, releasing Conger only a few meters away. Rehm swam to his friend, pulled him onto the dive mat, and headed for shore. Upon reaching the safety of the beach, it was clear that Conger had died as a result of his injuries. The direction from which the attack came suggested that the shark must have swum directly under Rehm prior to attacking and mortally wounding Omar Conger. This was the second White Shark attack from this recurring location. The San Mateo County coroner determined the cause of death to be

“exsanguination as the result of multiple shark bites. There

were multiple lacerations to the dorsal and palmar surfaces of the

hands, fingers and wrists ranging from 5 to 15 centimeters in length.

There were numerous lacerations to both posterior thighs and buttocks,

with the femoral vessels severed in both thighs.” The locations

of the wounds suggest that the shark first grabbed Conger by both

thighs, pulling him under the water. The injuries to the hands were

probably the result of his trying to fend off his assailant. Wound

dimensions suggest a White Shark 4.5 to 5 m in length.

Commercial divers Tisserand, age 38, and Scott Smith were aboard their boat 'Kandy Lou,' anchored 50 to 70 m from shore, on the northwest side of the island in 6 to 7 fm of water, with a visibility of 3 to 4 m. There was an overcast sky and a 10-to-15-knot wind that occasionally caused whitecaps on the 1-to-2 m groundswells. Tisserand had been watching about 20 pinnipeds 30 to 40 m southeast of his location, with a second, similar group midway between the boat and shore. Both groups of pinnipeds had attracted the divers' attention because they seemed very agitated and nervous. Tisserand reported, "They were barking and looking quickly about the surface and below the water." At 1200 hrs, Tisserand and Smith made an exploratory dive to determine the site's potential for collecting abalone. Tisserand was dressed in a black wetsuit, swim fins, and mask with snorkel, and carried an abalone net basket, pry bar, and a bang stick. His regulator was attached to a yellow hookah airline. Smith wore a blue wetsuit, black swim fins, and mask, and utilized yellow scuba tanks. Tisserand recalled: "The bottom was rocky, reef like, with many small caves and short kelp plants covering most of the bottom. I saw 15 to 20 seals on or very near the bottom. They appeared distressed by something, as they kept looking up toward the surface while remaining on the bottom in the kelp grass. Some of the seals moved slowly through the kelp grass by using their front flippers to pull themselves along the bottom. I felt very uncomfortable and returned to the boat after 10 minutes." Due to their shared apprehension, Tisserand and Smith discussed moving to a new location. However, after a 15 to-20-minute discussion and rest period, they decided to dive the area. Surgeon John Leonard reported, "Upon arrival at the hospital's

emergency room, Tisserand was alert and in a mild state of shock.

He had suffered 11 multiple tooth punctures to the lower left leg,

with a traumatic compound fracture dislocation [near- amputation]

of the left ankle, with only 30 to 40% of the tissue and epidermis

on the inside of the ankle intact." Following several surgical

procedures and treatment with antibiotics, the diver was discharged

from the hospital on 19 September. Whether Tisserand suffered permanent

impairment is unknown.

Johnson had been submerged for about five minutes, working with his head down and feet raised toward the surface. He was attempting to pry several abalone from the underside of a ledge when he felt something grab his right swim fin and shake it vigorously. He turned and looked back toward the surface to see what had grabbed him. A large White Shark released his fin and passed very close to the diver before disappearing from view in the murky water. Johnson began tugging on his airline in hopes of drawing the attention of his tender. He kept spinning around, trying to keep sight of the shark, which returned from time to time, passing very quickly and close to the diver. Johnson thought the White Shark was 5 to 6 m in length. It made five additional passes at the diver following its initial strike before it finally departed. The diver surfaced and was taken aboard his boat. Although he suffered no physical injury, his swim fin bore five individual thin slices to the upper and lower surfaces.

They approached the rock from the south, passing very close to it as they circled, looking for a suitable anchorage. This maneuver frightened several of the Harbor Seals that had been sunning on the rock, causing them to enter the water. Rebstock and his three companions then anchored their boat about 10 m south of Perch Rock. Rebstock was dressed in a black wetsuit with hood and boots, mask, weight belt and flotation vest with green swim fins, a scuba tank and regulator, and carried a yellow pole spear and white game bag. He entered the water by rolling backward out of the boat. Rebstock surfaced 1 m from his boat and trod water while his companions handed him some additional equipment. About one minute after the diver's entry into the water, a White Shark, 5 to 6 m in length, came from directly beneath him, striking with such force that both the diver and shark rose 1 to 2 m out of the water. The shark released Rebstock at the height of its breach, arching its back to re-enter the water nose first. The diver was thrown from amidships to the stern, a distance greater than 3 m. He was immediately pulled aboard, the anchor rope was cut, and the boat headed for Government Point. The pattern and arrangement of these individual punctures is consistent with the victim's leg having been bent at the knee (treading water) when the shark struck from directly below, causing the anterior surface of Rebstock's lower leg (shin) to be depressed against the teeth in the shark's lower jaw. Further, because the wounds are smooth-edged, razor-like cuts, there must have been very little movement of the shark relative to the victim while his leg was in contact with the shark's teeth. Interspace measurements (the distance from the centers of adjacent tooth punctures) of the wounds were comparable to tooth interspace measurements (the distance between adjacent tooth tips) of a White Shark 5.8 m in length. Physicians were confident of a complete recovery for the scuba diver. Today, Robert Rebstock practices law in Santa Barbara. It is not possible to positively determine whether the shark that

attacked Gary Johnson on July 19 was the same individual that then

attacked Robert Rebstock on the 23rd, four days later. However, research

conducted at the Farallon Islands off San Francisco suggests that

some White Sharks remain within a given home range during certain

times of the year, for varying lengths of time. Although no direct

evidence exists, the short four-day period between the attacks on

Johnson and Rebstock at Point Conception, together with the size estimates

of the attacking shark by the victims and witnesses, strongly suggest

that a single White Shark might have been responsible for both attacks.

At 1000 hours Schupe and his boat tender, Glenn Meyer, had positioned their boat about 30 meters from Castle Rock in 8 fathoms of water with 3 to 5 meters of visibility. There was a light breeze with 2-to-3-meter groundswells and a calm sea surface. There were over 100 sea lions in the area. Schupe was dressed in a full wetsuit with hood, mask, boots and swim fins and was attached to a hookah airline. The sky was clear. Schupe recalled, "I had only been down about six minutes and was over a jumbled rock formation with a lot of kelp and a few sandy areas here and there. I was working at about a 45-degree angle with my feet pointing up and my head down. I was collecting red urchins when I felt a strong tug on my left fin. Thinking it might be a seal, I looked up to see a shark swimming away. I immediately looked at my depth gauge, which read exactly 47 feet [14.3 meters], so I would know how quickly I could ascend without getting the bends. I headed for the surface while continually looking for the shark. I surfaced about 75 feet [25 meters] from the rock, but my boat had drifted about 50 to 75 feet [about 16 to 25 meters] away from where it had originally been located. I swam to the boat and pulled myself on board." The diver removed his fin and boot and used hydrogen peroxide to wash the wound. It was wrapped, and they departed for Santa Barbara Harbor. After they docked their boat the injured diver was taken to his family physician, Kirk Gilbert; Schupe had called while en route to the harbor. The punctures to his left foot required 26 sutures. Schupe observed the shark for only a few fleeting seconds before it disappeared in the "murky" water. "As I watched it swim away I think it was 7 to 8 feet [about 2.5 meters] long with a dark gray back, and 18 to 24 inches [45 to 60 centimeters] in girth." His swim fin received a 7-centimeter cut, with a triangular tooth impression evident on the underside. Although the tooth impression suggests a White Shark, the species of shark responsible for this attack could not be positively identified. Schupe still dives commercially off the Pacific Coast.

It was Saturday, 8 September 1990, at 1300 hours, under a clear sky with an air temperature of 11°C. According to the abalone free diver, there was a strong, steady wind of at least 20 knots, with some gusts exceeding 30 knots. He was 200 meters from shore at Russian Gulch Beach, near Jenner, Sonoma County, California (38°28.5'N; 123°10.5'W). The water was 6 to 8 fathoms deep, with a visibility of 3 to 4 meters. The ocean floor was rocky, with thinly scattered Palm Kelp (Postelsia palmaeformis) and Bull Kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) throughout the general dive area. Orr was dressed in a full black wetsuit with hood, mask, boots, weight belt, and swim fins. Pinnipeds were seen on several large rocks 200 meters north of Orr's location. Orr had been diving for about an hour and had collected four abalone. He was returning to spear fish he had spotted during earlier dives. Orr entered the water off the starboard side of his dive board (used to hold diving equipment) and slowly drifted until 3 meters away from it. He was face down when the water seemed to explode all around his head. Orr's head and shoulders were lifted from the water and he was pushed across the surface at a rapid rate. His vision cleared just for a moment, allowing him to see water rushing under his head. A single, triangular tooth blocked most of the vision of Orr's right eye, as he realized that his head was in a shark's mouth. According to Orr, "Within two or three seconds I found myself being 'driven' across the surface toward my board." The shark, with the diver still in its mouth, struck the board and continued for another 10 to 15 meters before releasing its grip. During the attack, Orr continually struck the shark on the side of its head until he was released. Once free of the shark, he watched it slowly descend out of sight. Orr swam to his board, which was upside down, and pulled himself up onto its exposed bottom. Because the anchor line was fouled, he anxiously slipped off the board and into the water, righted it, retrieved a knife from its sealed compartment, cut the anchor line, and headed for shore. Blood was flowing freely from his head wounds, obstructing his vision . While paddling to shore, he saw the 4-meters White Shark off to his left, swimming slowly toward the open sea. It took Orr about 20 minutes to reach the beach. After walking 20 meters up the sand, he yelled to several bathers to summon help. At that same moment, Orr noticed a California Highway Patrol vehicle heading south on State Highway 1, which parallels the beach. He waved his arms, attracting the attention of the patrolmen, who dispatched a Sonoma County Sheriff's Department helicopter. The injured diver was transported to Santa Rosa Community Hospital in Santa Rosa. It might be said that Rodney Orr is "a man of the sea,"

for he returned to free diving a mere five days following his attack.

As of this writing, Rodney Orr still dives the Central California

coast.

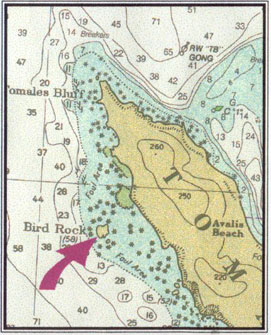

Tinley, Karol Knox and Charles Wilson had spent the morning riding the flood tide into Tomales Bay, scouting for California Halibut (Paralichthys californicus). They experienced a number of unsuccessful passes through the mouth of Tomales Bay and four fruitless exploratory dives off the east side of Bird Rock. Undaunted, the persistent abalone hunters moved their 4-meter inflatable Avon to the south side of the rock. Tinley rolled off the starboard side of the boat and proceeded to the bottom, where he collected two abalone. He surfaced on the starboard side of the inflatable, between the boat and Bird Rock. There he measured a suspected "clicker abalone" (under 18 centimeters legal size). After confirming the legal size of the suspect abalone, Tinley dived to a depth of about 3 fathoms, where he noticed something to his left. The diver had been in the water about five minutes. He quickly recognized the silhouette of a large White Shark, 4 to 5 meters in length, below him in the water column. The shark abruptly turned and charged upward toward the diver. Within a heartbeat, the shark held Tinley firmly in its jaws as it continued its upward trajectory. Instinctively, Tinley had thrown his hands out in front of his body to ward off the impending attack. He recalled, "It happened so damn fast I don't remember my position in the shark's mouth, or even remember any feeling of pain or pressure." Within 2 meters of the surface, the shark repurchased its hold on the diver, much as a dog plays tug-of-war with an old sock. The shark released the diver abruptly and swam off. Tinley quickly swam the 5 meters to reach the inflatable, where he was helped aboard. Once on board, Tinley - a registered trauma-room nurse - began assessing his own injuries. His left shoulder and forearm had been badly lacerated, and his left abdomen had an open wound. A hand-held VHF marine radio was used to place an emergency "mayday" call over channel 16. The USCG informed the caller that its helicopter was currently on call and would not be able to transport the injured diver to a hospital for some time. Because of this delay, the Sonoma County Sheriff's Department helicopter, Henry One, was dispatched to Tomales Point at 1138 hours, arriving on the scene at 1155 hours. Tinley was placed aboard and airlifted to Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital in Santa Rosa, arriving at 1229 hours.

One of the most intriguing shark attack cases from the Pacific Coast of North America occurred over 40 years ago and has remained somewhat enigmatic for some shark researchers. To clear up several of the myths and misconceptions that surround this incident, a description and summation of this attack seemed appropriate. On Sunday, 14 June 1959, Robert Pamperin, age 33, was free diving for abalone in 6 to 7 fathoms of water. The water featured 7 meters of visibility and a temperature of 20°C. At 1710 hours, Pamperin and his diving companion, Gerald Lehrer, age 30, were about 50 meters from shore at Alligator Head. The temperature of the air was 21°C and there was a light overcast. Pamperin was wearing blue swim fins, a pink bathing suit, a black mask and black diving gloves, and carried a yellow-handled abalone iron. A black inner tube, with an attached burlap sack, was being utilized by the two divers and was also in the same area.

The divers had slowly drifted away from one another until separated by 10 to 15 meters, with Lehrer 20 meters from the point and Pamperin 30 to 40 meters. Unexpectedly, Lehrer heard Pamperin yell out, "Help me!" Turning quickly in the direction from which he heard the voice, he saw his companion upright and unnaturally high out of the water, with his mask missing. Lehrer began swimming toward his friend, thinking he might have a cramp. While looking at Pamperin, Lehrer later recounted, "Suddenly everything was moving in slow motion." He watched in disbelief as his friend slowly disappeared beneath the surface of the crimson water. Startled, Lehrer quickly dived beneath the surface to see Pamperin in the jaws of a shark he estimated to be more than 7 meters in length. As this drama was unfolding, William Abitz stood on an elevated rock formation that overlooked the attack site. He was alerted to the event by Pamperin's cries for help. Abitz recounted, "Pamperin was thrashing as if he were trying to run away from something, then he disappeared below the surface." In the water, Lehrer could see his friend in the mouth of the shark, his legs not visible. He surfaced just long enough to gasp a breath of air, then dived under to try and help his friend. He observed the shark lying in a sandy area on the bottom, jerking from side to side. It appeared the shark was trying to either swallow or spit out Pamperin. Lehrer returned to the surface, inhaled air and dived under the water again. He swam toward the bottom, waving his arms frantically in an attempt to frighten the shark away, but it ignored him and kept twisting back and forth. Realizing nothing could be done, Lehrer swam toward the beach, being met 10 to 15 meters from shore by Abitz, who had swum out to assist the diver. Upon reaching shore, they located lifeguards, who informed local authorities of the attack. Within less than an hour, 10 highly qualified scuba divers, including Conrad Limbaugh of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, spent an estimated two hours searching the attack location in an unsuccessful attempt to locate the victim. United States Coast Guard helicopter pilot Harold B. MacDuffy observed a blue swim fin floating at the surface, as well as a dead seal or Sea Lion (Zalophus californicus), but did not see any sharks. Several hours following the attack, Pamperin's inner tube, containing two abalone (Haliotis sp.), was recovered at the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club. Following the attack on Pamperin, much deliberation was - and since then has been - given by researchers to the species of shark responsible for this attack. This uncertainty may be due to its close proximity in time to Albert Kogler's fatal attack just one month earlier or to several unsubstantiated rumors. In either case, the following is what is known about the shark, the attack location and some related circumstances, which until now have gone unreported.

The estimated length of the attacking shark

precludes almost all known potentially dangerous species common to the

Pacific Coast, except the Tiger and White sharks. At best, the Tiger Shark

(Galeocerdo cuvier) is only an infrequent, if not rare, visitor to Southern California, while

the White Shark is frequently observed and captured off the southern

coast. Excluding the blunt nose, which could have been obscured by the

victim, the description of Lehrer's shark more closely approximates the

appearance of a White Shark rather than a Tiger. Further, Lehrer did not

remember any markings on the shark, including vertical stripes often

visible on the flanks of adult Tiger Sharks. He also told investigators

that he could see Pamperin and the shark, including "its jaws and

jagged teeth,"

quite clearly as they lay on the bottom 10 to 15 meters from his

location. Comparison of Tiger Shark and White The reference to the shark's being as big as a Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) would seem to further support a White Shark as being the assailant. This interpretation assumes that the reference pertains to the shark's coloration, length, and girth, appearing similar to that of a Killer Whale. Contrast between the black and white patterns for both White Sharks and Killer Whales is similarly striking, as is the general body shape, especially when observed during the stressful, fleeting moments of a shark attack. These conclusions would seem to implicate a White Shark as the causal species. Eyewitness testimony in support of this identification was obtained from the following newspaper article, which should put the question of shark species to rest. Because of the confusion that persisted for several days in local newspapers with certain aspects of the attack, Gerald Lehrer granted a final interview to the San Diego Evening Tribune on 18 June 1959. Lehrer emphatically stated, "What I saw was a White Shark. I don't understand the confusion. The first time I was shown pictures of different kinds of sharks, I immediately recognized the White Shark. I have never said anything else, but I have read and heard all kinds of speculation about other kinds of sharks. It was a White Shark." There would seem to be little doubt that a White Shark 6 to 7 meters in length was responsible for Robert Pamperin's fatal shark attack. If you, or someone you know, has been involved in a shark attack and would like to voluntarily participate in the Shark Research Committee's research program, please use the appropriate reporting form. |

Over

a 15 day period in 1984, four shark attacks — one of them fatal

— occurred off the Pacific Coast of the United States. The drama

would begin on Saturday, 15 September 1984, with the death of 28-year-old

abalone free diver Omar Conger.

Over

a 15 day period in 1984, four shark attacks — one of them fatal

— occurred off the Pacific Coast of the United States. The drama

would begin on Saturday, 15 September 1984, with the death of 28-year-old

abalone free diver Omar Conger.  On

Saturday, 9 September 1989, commercial diver Mark Tisserand was attacked

by a White Shark at Southeast Farallon Island, off San Francisco (37°

42.1'N; 123°00.8'W). This would be the sixth attack from this recurring

location and the final shark attack of the 1980s.

On

Saturday, 9 September 1989, commercial diver Mark Tisserand was attacked

by a White Shark at Southeast Farallon Island, off San Francisco (37°

42.1'N; 123°00.8'W). This would be the sixth attack from this recurring

location and the final shark attack of the 1980s. Tisserand

entered the water and began descending vertically, feet first. Smith

followed him some 15 to 20 seconds later. Tisserand was 3 to 4 m from

the bottom when "suddenly I felt a vise like pressure on my

left leg and knew immediately what had happened." A White

Shark, 4 to 5 m in length, shook Tisserand for 10 to 15 seconds. He

struck the shark's head with the butt of his bang stick. The diver

was unable to release the safety pin to discharge the weapon's explosive

head. The shark released its grip on Tisserand at about the same time

Smith was entering the water. At mid depth, Smith saw Tisserand rapidly

ascending and, 3 to 5 m below him, glimpsed a White Shark swimming

away. Smith observed the shark three more times during the 30-m swim

to the boat. The shark swam slowly and smoothly at all times and did

not attempt to bite either diver. When they were aboard the boat,

a tourniquet was applied to Tisserand's leg and an emergency called

was placed by radio to the U.S. Coast Guard. A U.S. Navy helicopter,

piloted by Cmdr Michael Rogers and Lt. Cmdr. Kirk Wessle, was dispatched

from Alameda Naval Air Station. Rescue Swimmer AW2 Henry Wilson was

deployed to swim and recover Tisserand from the boat. The helicopter

picked up the victim and flew him to Peninsula Hospital in Burlingame.

Tisserand

entered the water and began descending vertically, feet first. Smith

followed him some 15 to 20 seconds later. Tisserand was 3 to 4 m from

the bottom when "suddenly I felt a vise like pressure on my

left leg and knew immediately what had happened." A White

Shark, 4 to 5 m in length, shook Tisserand for 10 to 15 seconds. He

struck the shark's head with the butt of his bang stick. The diver

was unable to release the safety pin to discharge the weapon's explosive

head. The shark released its grip on Tisserand at about the same time

Smith was entering the water. At mid depth, Smith saw Tisserand rapidly

ascending and, 3 to 5 m below him, glimpsed a White Shark swimming

away. Smith observed the shark three more times during the 30-m swim

to the boat. The shark swam slowly and smoothly at all times and did

not attempt to bite either diver. When they were aboard the boat,

a tourniquet was applied to Tisserand's leg and an emergency called

was placed by radio to the U.S. Coast Guard. A U.S. Navy helicopter,

piloted by Cmdr Michael Rogers and Lt. Cmdr. Kirk Wessle, was dispatched

from Alameda Naval Air Station. Rescue Swimmer AW2 Henry Wilson was

deployed to swim and recover Tisserand from the boat. The helicopter

picked up the victim and flew him to Peninsula Hospital in Burlingame. On Saturday, 19 July 1975, commercial abalone diver Gary Johnson,

age 34, would be attacked at Point Conception, Santa Barbara County,

California (34°26.6'N; 120°28.5'W) at about 1330 hrs. This site would

become a recurring location only four days later. Johnson wore a black

wetsuit with hood, boots, swim fins, and a mask with a stainless steel

rim, and carried an abalone net basket and gray aluminum abalone iron.

His air was supplied by a hookah line with regulator. The diver observed

several Harbor Seals basking on Perch Rock as he gently lowered himself

into the water. He was about 400 to 450 m from shore, in water 4 to

5 fm deep, with a visibility of 4 to 6 m.

On Saturday, 19 July 1975, commercial abalone diver Gary Johnson,

age 34, would be attacked at Point Conception, Santa Barbara County,

California (34°26.6'N; 120°28.5'W) at about 1330 hrs. This site would

become a recurring location only four days later. Johnson wore a black

wetsuit with hood, boots, swim fins, and a mask with a stainless steel

rim, and carried an abalone net basket and gray aluminum abalone iron.

His air was supplied by a hookah line with regulator. The diver observed

several Harbor Seals basking on Perch Rock as he gently lowered himself

into the water. He was about 400 to 450 m from shore, in water 4 to

5 fm deep, with a visibility of 4 to 6 m.  Physicians

at Lompoc Hospital described Rebstock's most severe injury as "a

single deep laceration to the outer surface of the upper thigh. This

wound is shaped like an upside-down 'J' and is about 6 inches

[15 cm] in length. This injury penetrated deep into musculature,

but did not involve any major nerves or vascular vessels. The second

injury was to the front of his lower left leg, consisting of multiple

tooth punctures. They range in length from 0.5 to 2 inches [1.25

to 5 cm] and were 0.5 to 1.5 inches [1.25 to 3.75 cm] deep."

Physicians

at Lompoc Hospital described Rebstock's most severe injury as "a

single deep laceration to the outer surface of the upper thigh. This

wound is shaped like an upside-down 'J' and is about 6 inches

[15 cm] in length. This injury penetrated deep into musculature,

but did not involve any major nerves or vascular vessels. The second

injury was to the front of his lower left leg, consisting of multiple

tooth punctures. They range in length from 0.5 to 2 inches [1.25

to 5 cm] and were 0.5 to 1.5 inches [1.25 to 3.75 cm] deep."

On Thursday,

29 October 1992, commercial urchin diver Andy Schupe, age 40, was

attacked off Castle Rock, San Miguel Island, Santa Barbara County,

California (34°03.2'N; 120°26.3'W). This would be the first of three

shark attacks that would occur off the Pacific Coast over a period

of 16 days. It would also be the third attack from this recurring

location.

On Thursday,

29 October 1992, commercial urchin diver Andy Schupe, age 40, was

attacked off Castle Rock, San Miguel Island, Santa Barbara County,

California (34°03.2'N; 120°26.3'W). This would be the first of three

shark attacks that would occur off the Pacific Coast over a period

of 16 days. It would also be the third attack from this recurring

location.  On

Wednesday, 4 December 1991, commercial urchin diver David Abernathy,

age 25, was attacked by a White Shark at Shelter Cove, between Eureka

and Fort Bragg in northwestern California (40°01.7'N; 124°05.0'W).

Abernathy, accompanied by boat owner Joe Lara and tender Gerald Vickers,

had been diving for about six hours. He was dressed in a black wetsuit,

hood, boots, swim fins, mask, and weight belt. The diver was attached

to a hookah airline and carried an urchin rake. Under a sunny sky,

the sea surface was calm with 1-to-2-meter groundswells rolling rhythmically

over the sandy ocean floor. Air and water temperatures were estimated

at 15ºC and 10ºC, respectively. The water was 8 fathoms deep with

visibility of 5 meters.

On

Wednesday, 4 December 1991, commercial urchin diver David Abernathy,

age 25, was attacked by a White Shark at Shelter Cove, between Eureka

and Fort Bragg in northwestern California (40°01.7'N; 124°05.0'W).

Abernathy, accompanied by boat owner Joe Lara and tender Gerald Vickers,

had been diving for about six hours. He was dressed in a black wetsuit,

hood, boots, swim fins, mask, and weight belt. The diver was attached

to a hookah airline and carried an urchin rake. Under a sunny sky,

the sea surface was calm with 1-to-2-meter groundswells rolling rhythmically

over the sandy ocean floor. Air and water temperatures were estimated

at 15ºC and 10ºC, respectively. The water was 8 fathoms deep with

visibility of 5 meters.  Most

of us are familiar with the expression "He went to the well

once too often." This adage is usually associated with a

questionable decision made by a coach or player during a football

or baseball game. It could also apply to free diver Rodney Orr, age

49, who was attacked a second time by a White Shark very near the

location of his first attack many years earlier, in 1961.

Most

of us are familiar with the expression "He went to the well

once too often." This adage is usually associated with a

questionable decision made by a coach or player during a football

or baseball game. It could also apply to free diver Rodney Orr, age

49, who was attacked a second time by a White Shark very near the

location of his first attack many years earlier, in 1961.  Physician

Michael Jay was assigned to the hospital's trauma room and attended

to the injured diver. Orr had received multiple tooth punctures to

the face, neck, scalp and upper shoulder. His wounds were cleaned

and dressed, with several requiring sutures. Orr was administered

antibiotics by injection and given a prescription for continuing them

for one week. Physicians did not consider his injuries life-threatening,

nor was overnight hospitalization necessary. Jay expected the diver

to make a full recovery.

Physician

Michael Jay was assigned to the hospital's trauma room and attended

to the injured diver. Orr had received multiple tooth punctures to

the face, neck, scalp and upper shoulder. His wounds were cleaned

and dressed, with several requiring sutures. Orr was administered

antibiotics by injection and given a prescription for continuing them

for one week. Physicians did not consider his injuries life-threatening,

nor was overnight hospitalization necessary. Jay expected the diver

to make a full recovery.  Abalone

sport free diver Colum Tinley, age 36, was hunting on the south side

of Bird Rock, at Tomales Point in Marin County north of San Francisco

(38°13.7'N; 122°59.7'W). It was there, on Tuesday, 13 August 1996,

at 1115 hours, that he was attacked by a large White Shark. Tinley

was 30 meters from shore in water 5 to 6 fathoms deep with 5 meters

of visibility and a estimated temperature of 12°C. The ocean floor

was primarily rocky, with some scattered short-stature kelps. The

sea was calm with a 0.5-to-1-meter groundswell. The sky was overcast

and foggy with a temperature of about 16°C. This was the ninth White

Shark attack on a diver from the Tomales Point "recurring location."

Abalone

sport free diver Colum Tinley, age 36, was hunting on the south side

of Bird Rock, at Tomales Point in Marin County north of San Francisco

(38°13.7'N; 122°59.7'W). It was there, on Tuesday, 13 August 1996,

at 1115 hours, that he was attacked by a large White Shark. Tinley

was 30 meters from shore in water 5 to 6 fathoms deep with 5 meters

of visibility and a estimated temperature of 12°C. The ocean floor

was primarily rocky, with some scattered short-stature kelps. The

sea was calm with a 0.5-to-1-meter groundswell. The sky was overcast

and foggy with a temperature of about 16°C. This was the ninth White

Shark attack on a diver from the Tomales Point "recurring location."

After he was admitted to the hospital's trauma room, it was quickly determined that Tinley's blood pressure was low and he was in a state of shock. He had received five tooth lacerations involving the deep tissue of his left shoulder, six lacerations to his left forearm, two lacerations of his left hand, and a large cut to the left side of his lower abdomen. Several hours of surgery was required to repair the damage to Tinley's nerves, ligaments, tendons, vascular vessels, and the soft tissue of his shoulder, arm, hand, and abdomen. During the operation, surgeon James Harwood removed three small tooth fragments from the laceration in the diver's left shoulder.

After he was admitted to the hospital's trauma room, it was quickly determined that Tinley's blood pressure was low and he was in a state of shock. He had received five tooth lacerations involving the deep tissue of his left shoulder, six lacerations to his left forearm, two lacerations of his left hand, and a large cut to the left side of his lower abdomen. Several hours of surgery was required to repair the damage to Tinley's nerves, ligaments, tendons, vascular vessels, and the soft tissue of his shoulder, arm, hand, and abdomen. During the operation, surgeon James Harwood removed three small tooth fragments from the laceration in the diver's left shoulder.  The fragments not only substantiate Tinley's identification of his attacker, but also assist in determining the length of the attacking White Shark to be about 6 meters. In October 1996, Colum Tinley underwent a surgical nerve graft to repair a severed posterior interosseous nerve, returning about 90 percent of normal function to his left hand.

The fragments not only substantiate Tinley's identification of his attacker, but also assist in determining the length of the attacking White Shark to be about 6 meters. In October 1996, Colum Tinley underwent a surgical nerve graft to repair a severed posterior interosseous nerve, returning about 90 percent of normal function to his left hand.

The

following four events occurred prior to the attack on Pamperin and

may have been contributory. First, fewer than two hours before the

attack, several Yellowtail (Seriola dorsalis) were speared

by divers near the attack site. In addition to body fluids, the low-frequency

vibrations produced by a speared fish are known to attract sharks.

Second, an hour prior to the attack, a U.S. Navy sailor swimming off

nearby rocks had badly lacerated himself, losing a considerable amount

of blood while in the water. Third, 600 meters west of the cove is

a small rookery of Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina), a known prey

of several apex marine predators. The fourth and final event might

have been more contributory to the attack than any of the others.

A dead whale (species unknown) washed up the night before onto the

beach at La Jolla Shores, 800 meters north of where Pamperin was attacked.

Surface currents and overnight winds could have dispersed the whale's

body fluids to much of the cove, in addition to probably producing

a "chum slick," or "odor corridor," to the open sea

many hours before the attack. The untimely beaching of the whale could

have attracted the predator responsible for this tragedy from many

kilometers distant. The description of the shark, as given by Lehrer,

is "over 20 feet [7 meters] in length with a white belly,

grading to an even dark gray or black on top, with a blunt nose."

He told the San Diego Union newspaper, "It was so big I thought

at first it was a Killer Whale. It had a white belly and I could see

its jaws and jagged teeth." Lehrer could recall no other blotches

or markings on the shark.

The

following four events occurred prior to the attack on Pamperin and

may have been contributory. First, fewer than two hours before the

attack, several Yellowtail (Seriola dorsalis) were speared

by divers near the attack site. In addition to body fluids, the low-frequency

vibrations produced by a speared fish are known to attract sharks.

Second, an hour prior to the attack, a U.S. Navy sailor swimming off

nearby rocks had badly lacerated himself, losing a considerable amount

of blood while in the water. Third, 600 meters west of the cove is

a small rookery of Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina), a known prey

of several apex marine predators. The fourth and final event might

have been more contributory to the attack than any of the others.

A dead whale (species unknown) washed up the night before onto the

beach at La Jolla Shores, 800 meters north of where Pamperin was attacked.

Surface currents and overnight winds could have dispersed the whale's

body fluids to much of the cove, in addition to probably producing

a "chum slick," or "odor corridor," to the open sea

many hours before the attack. The untimely beaching of the whale could

have attracted the predator responsible for this tragedy from many

kilometers distant. The description of the shark, as given by Lehrer,

is "over 20 feet [7 meters] in length with a white belly,

grading to an even dark gray or black on top, with a blunt nose."

He told the San Diego Union newspaper, "It was so big I thought

at first it was a Killer Whale. It had a white belly and I could see

its jaws and jagged teeth." Lehrer could recall no other blotches

or markings on the shark. Shark dentition demonstrates the

improbability of Lehrer's being able to see any teeth from a distance of 10 meters or

more except those of a large White Shark. According to fossil-shark researcher

Gordon Hubbell, the enamel height of White Shark teeth is almost twice that of a

Tiger Shark at comparable body lengths (Photograph courtesy Gordon Hubbell).

Shark dentition demonstrates the

improbability of Lehrer's being able to see any teeth from a distance of 10 meters or

more except those of a large White Shark. According to fossil-shark researcher

Gordon Hubbell, the enamel height of White Shark teeth is almost twice that of a

Tiger Shark at comparable body lengths (Photograph courtesy Gordon Hubbell).