| |

Unprovoked White Shark Attacks on Swimmers

Although swimmers certainly composed the largest number of potential shark attack victims to use the waters of the Pacific Coast during the Twentieth Century, only 12 authenticated attacks against this group were recorded. The causal species of sharks for these 12 attacks consisted of 6 unknown and 6 that implicated the White Shark. For the 6 cases in which the White Shark was positively identified or highly suspect as the species responsible, 3 of the attacks were fatal.

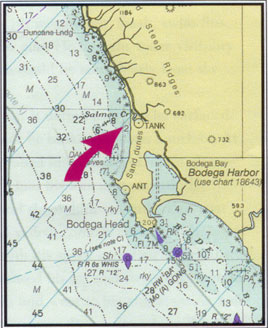

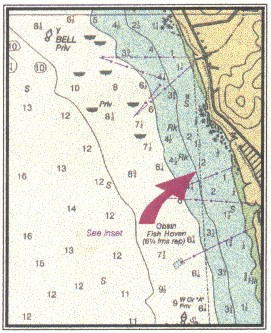

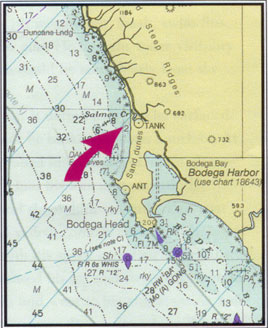

It was

a pleasant Sunday morning, 20 August 1961. David Vogensen, age 16,

decided to go for a swim, accompanied by several friends. They had

swum out to a sandbar about 75 meters from the beach and were returning

to shore. The young swimmers crossed over a channel to a location

about 6 meters from the beach near Salmon Creek, Sonoma County, California

(38°20.8'N; 123°04.5'W). It was about 0930 hours and the water was cold

and very clear.Vogensen was wearing dark blue swimming trunks. It was

a pleasant Sunday morning, 20 August 1961. David Vogensen, age 16,

decided to go for a swim, accompanied by several friends. They had

swum out to a sandbar about 75 meters from the beach and were returning

to shore. The young swimmers crossed over a channel to a location

about 6 meters from the beach near Salmon Creek, Sonoma County, California

(38°20.8'N; 123°04.5'W). It was about 0930 hours and the water was cold

and very clear.Vogensen was wearing dark blue swimming trunks.

He saw the shark swim over the sandbar and parallel the beach until

about 10 meters from his location. The youth observed a large dark shape,

a few feet below the surface, approaching him head-on. The shark circled

Vogensen twice before grasping the lower groin and upper inner thighs

of both legs. It held its victim for several seconds before it began

mouthing his left leg down to the ankle. The youth was unaware of

any sensation of pain, only a great deal of pressure, until his foot

went numb. It was then that he knew a shark had bitten him. What he

did not know was the extent of his injuries. Vogensen made his way

up the beach, where he collapsed, clutching his bloody trunks. From

this time until hours later in the hospital, events were unclear to

the young man.

The swimmer was taken by automobile to Palm Drive Hospital in Sebastopol

for emergency trauma care. Following emergency treatment, he was transferred

to Hillcrest Hospital in Petaluma. Vogensen had received numerous

slash wounds to his groin, with secondary lacerations to his left

leg and foot. Several tendons and nerves were traumatized, requiring

several hours of surgery to repair. Vogensen's physicians expected

a complete recovery without any physical limitations. The shark's

description and measurements of the wounds are indicative of a 4-meter

White Shark.

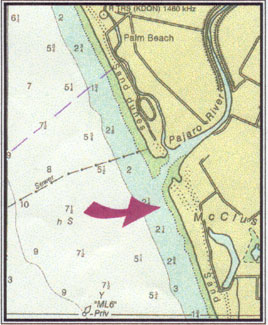

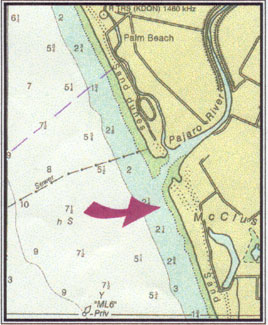

Pat DuNah, age 18, was bitten by a shark on Saturday, 5 August 1978, while swimming 30 meters from shore off Pajaro Dunes Beach, near Santa Cruz, California (36°51.6'N; 121°48.6'W). DuNah and two companion swimmers had decided to go body surfing. They swam out some 100 meters from the beach at about 1200 hours. The sky was overcast and the air warm, about 20°C, with a mild wind generating small ocean groundswells, creating water visibility of 3 to 5 meters. Pat DuNah, age 18, was bitten by a shark on Saturday, 5 August 1978, while swimming 30 meters from shore off Pajaro Dunes Beach, near Santa Cruz, California (36°51.6'N; 121°48.6'W). DuNah and two companion swimmers had decided to go body surfing. They swam out some 100 meters from the beach at about 1200 hours. The sky was overcast and the air warm, about 20°C, with a mild wind generating small ocean groundswells, creating water visibility of 3 to 5 meters.

They had been swimming and body surfing for 45 minutes when his two

companions decided to return to the beach; they had become too chilled

in the 15°C water to continue swimming. Wearing a blue bathing suit

with yellow trim, DuNah followed behind his companions as they headed

toward the beach. When he was 15 to 20 meters from the beach, about

to stand on the bottom in 0.5 fathoms of water, he felt a very strong

tug on his right leg. DuNah recalled that the tug "was almost violent

enough to knock me off my feet. Keeping a cool head...I panicked.

I never saw what hit me, so I headed for shore as fast as I could

swim. Upon reaching shore I noticed several small punctures and blood

on my leg."

A security guard from a business near the beach accompanied the victim to the Pajaro Dunes Fire Station, where DuNah was given first aid by paramedics. During this procedure, a paramedic took several measurements, noting that the small individual punctures were to both sides of the leg. The punctures formed a crescent about 18 centimeters in diameter. It was not necessary to suture any of the punctures. The wounds were cleaned and dressed by the firemen. The diameter of the bite, 18 centimeters, was the same on both sides of the leg, indicating a shark about 2 meters in length. The attack location and its history make it necessary to include the White Shark as a suspect in this attack. However, other species common to the area with the capacity for attacking humans include the Sevengill, Sixgill and Blue sharks. The causal species of shark could not be determined.

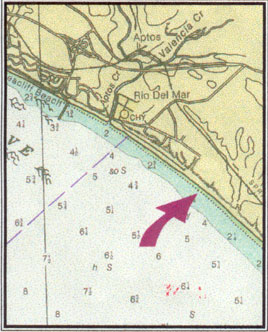

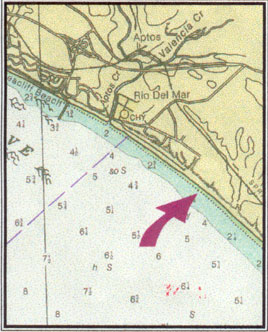

The

knowledge that female victims were only a small percentage of the

shark-attack cases reported in the ISAF by the end of the 1950s would

undoubtedly have been of little comfort to Susan Marie Theriot, age

16, on Thursday, 19 May 1960. On this day, Theriot became the first

known female to be attacked by a shark off the Pacific Coast in the

Twentieth Century. The attack occurred while she was swimming with

four student friends at Hidden Beach, near Aptos and Santa Cruz, in

Santa Cruz County, California (36°57.6'N; 121°53.7'W). It

was 1300 hours as Theriot and her companions were joined by 38 other

sophomores from Mora Central High School for a day of fun at the beach.

The beach outing was a reward for selling a specified number of their

high school yearbooks. Witnesses said Theriot was 40 to 50 meters from

shore in water 1 to 2 fathoms deep with a sandy bottom. The

knowledge that female victims were only a small percentage of the

shark-attack cases reported in the ISAF by the end of the 1950s would

undoubtedly have been of little comfort to Susan Marie Theriot, age

16, on Thursday, 19 May 1960. On this day, Theriot became the first

known female to be attacked by a shark off the Pacific Coast in the

Twentieth Century. The attack occurred while she was swimming with

four student friends at Hidden Beach, near Aptos and Santa Cruz, in

Santa Cruz County, California (36°57.6'N; 121°53.7'W). It

was 1300 hours as Theriot and her companions were joined by 38 other

sophomores from Mora Central High School for a day of fun at the beach.

The beach outing was a reward for selling a specified number of their

high school yearbooks. Witnesses said Theriot was 40 to 50 meters from

shore in water 1 to 2 fathoms deep with a sandy bottom.

A huge shark appeared just beneath the surface and circled the girl

several times before rushing in and seizing her left leg. Theriot

screamed to friends that something had grabbed her leg. Classmate

Larry Cronin was sitting in an inner tube near Theriot and grabbed

her by the arm, pulling her slightly up onto the tube with him. Tessie

Lettunich watched the shark circle the two swimmers several times.

She said, "It was awfully big, darkish gray, with a big fin

sticking out of the water." Theriot's blood quickly began

clouding the water around the inner tube as many students began screaming

for help. Most began kicking their feet wildly in an attempt to keep

the shark away as they all headed for the safety of the beach. When

they were only a few meters from shore, a large wave seemed to sweep

the students, simultaneously, up onto dry sand. Several students ran

up the beach to summon aid for their injured classmate.

Classmate Edward Cassef, age 16, applied a tourniquet to Theriot's

badly lacerated leg. The victim, unconscious from shock and loss of

blood, was transported by ambulance to Dominican Hospital in Santa

Cruz. A hospital official reported, "She was so weak we had

to build her up with blood transfusions before we could operate."

Several surgeons, including Paul J. Weiss, treated Theriot's extensively

traumatized leg, which ultimately had to be amputated below the knee.

The descriptions of the shark and the injury, provided by witnesses

and surgeons, clearly identified a 4-to-5-meter White Shark as the species

responsible for this attack.

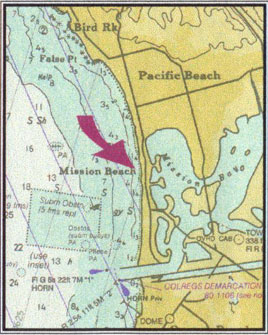

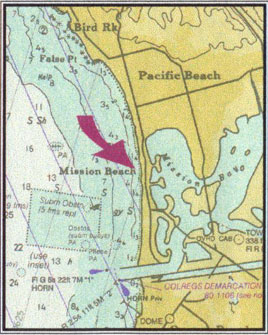

On Monday, 17 September 1984, at 1530 hours, Brian Cramer would be injured while

swimming at Mission Beach, a community in San Diego, California (32 47.1'

N; 11715.4'W). This was yet another instance where the identity of the attacking shark could

not be determined. Cramer was wading in waist-deep water when he felt something grab his

right arm near the elbow and violently shake it. A crescent-shaped wound, composed

of five individual tooth punctures, required many sutures for closure. The wound was 7.5 to

10 centimeters in diameter. The swimmer reported being in a school of baitfish when attacked. Cramer

said he could not see what had struck him because “the water was too murky to see anything

clearly.” Several biologists believed the attacker to be a small requiem

shark (Carcharhinidae). James Stewart, of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography,

considered a small Blue Shark (Prionace glauca) the most likely suspect, as “they

are frequently seen close inshore chasing baitfish.”Cramer’s injury was

minor, and physicians expected a complete recovery for the swimmer. Overnight

hospitalization was not required.

On Monday, 17 September 1984, at 1530 hours, Brian Cramer would be injured while

swimming at Mission Beach, a community in San Diego, California (32 47.1'

N; 11715.4'W). This was yet another instance where the identity of the attacking shark could

not be determined. Cramer was wading in waist-deep water when he felt something grab his

right arm near the elbow and violently shake it. A crescent-shaped wound, composed

of five individual tooth punctures, required many sutures for closure. The wound was 7.5 to

10 centimeters in diameter. The swimmer reported being in a school of baitfish when attacked. Cramer

said he could not see what had struck him because “the water was too murky to see anything

clearly.” Several biologists believed the attacker to be a small requiem

shark (Carcharhinidae). James Stewart, of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography,

considered a small Blue Shark (Prionace glauca) the most likely suspect, as “they

are frequently seen close inshore chasing baitfish.”Cramer’s injury was

minor, and physicians expected a complete recovery for the swimmer. Overnight

hospitalization was not required.

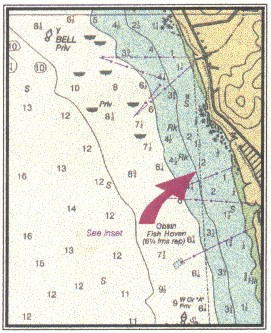

On Sunday, 28 April 1957, shock and

disbelief would grip one of California's small coastal communities. Peter

Savino, age 25, of Brooklyn, New York, would lose his life while swimming

with fellow California Polytechnic Institute student Daniel Hogan, age 22,

about 3 kilometers north of Morro Rock at 35th Street, Atascadero Beach, San Luis

Obispo County (35°24.2'N; 120°52.5'W). Savino and Hogan were accompanied

by 10 to 12 other student acquaintances for an early-afternoon ocean swim.

It was about 1330 hours on what was described by one companion as "a

very warm, sunny day." On Sunday, 28 April 1957, shock and

disbelief would grip one of California's small coastal communities. Peter

Savino, age 25, of Brooklyn, New York, would lose his life while swimming

with fellow California Polytechnic Institute student Daniel Hogan, age 22,

about 3 kilometers north of Morro Rock at 35th Street, Atascadero Beach, San Luis

Obispo County (35°24.2'N; 120°52.5'W). Savino and Hogan were accompanied

by 10 to 12 other student acquaintances for an early-afternoon ocean swim.

It was about 1330 hours on what was described by one companion as "a

very warm, sunny day."

The two swimmers encountered a very strongly ebbing tide that carried them

300 to 400 meters out to sea from their original location, which had been about 50 meters

from the beach. They decided it would be best to head back to shore before they

were swept out to sea any farther. Shortly after beginning their swim back

toward shore, Savino had become exhausted from fighting the current and was

being towed by his friend. Hogan recounted the events of the attack to Deputy

Sheriffs Don C. Miller and Henry Karagard as follows:

"Pete had gotten tired and was hanging onto

my shoulder when there was a sudden swirl of water and he disappeared

over the top of a big wave. I heard him yell, 'Something really big hit

me,' and I saw him raise an arm out of the water that was all bloody. I

saw the shark hit him. I said, 'Come on, let's get out of here,' because

I knew the blood would bring the shark back. I saw the shark, it boiled

the water around us and then it all got confused, but I saw the shark.

It carried Pete over a big wave. I started swimming toward shore and

Pete was right behind me. The next time I glanced back he was

gone."

Realizing nothing could be done, Hogan continued to the beach and informed

classmate Jerald Frank of the tragedy. Frank called a local mortuary, which then

notified the sheriff's office and the U. S. Coast Guard station in Morro Bay.

The USCG dispatched the cutter Alert, which, upon

arriving on the scene, lowered a 6.5-meter launch under the command of

Executive Officer James C. Knight. Within mere minutes of beginning their

search for the missing swimmer, Knight reported, "We located a shark

as long as our launch. After making a quick trip back to the Alert for

firearms we returned to the area where we had last seen the shark, but it

was gone."  Knight was positive that the shark

observed was not a Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus), as was

reported in several newspaper accounts of the attack. Knight also reported

sighting several smaller Blue Sharks in the search area. The search resumed the

following day, but was unsuccessful. Savino's body was never recovered. Knight was positive that the shark

observed was not a Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus), as was

reported in several newspaper accounts of the attack. Knight also reported

sighting several smaller Blue Sharks in the search area. The search resumed the

following day, but was unsuccessful. Savino's body was never recovered.

It is not possible to unequivocally determine the species of shark

responsible for this incident. The shark's length, about 6 meters, probably precluded

most untrained observers in the 1950s from considering any species of shark

except a Basking Shark. However, Executive Officer Knight was familiar with

Basking Sharks and was positive that the shark he observed was not this species.

There are some striking similarities between this case and Robert Pamperin's

fatal White Shark attack in 1959. A large White Shark is highly

suspect in Peter Savino's fatal attack.

If you, or someone you know, has been involved in a shark attack and would

like to voluntarily participate in the Shark Research Committee's research

program, please use the appropriate reporting form.

|

It was

a pleasant Sunday morning, 20 August 1961. David Vogensen, age 16,

decided to go for a swim, accompanied by several friends. They had

swum out to a sandbar about 75 meters from the beach and were returning

to shore. The young swimmers crossed over a channel to a location

about 6 meters from the beach near Salmon Creek, Sonoma County, California

(38°20.8'N; 123°04.5'W). It was about 0930 hours and the water was cold

and very clear.Vogensen was wearing dark blue swimming trunks.

It was

a pleasant Sunday morning, 20 August 1961. David Vogensen, age 16,

decided to go for a swim, accompanied by several friends. They had

swum out to a sandbar about 75 meters from the beach and were returning

to shore. The young swimmers crossed over a channel to a location

about 6 meters from the beach near Salmon Creek, Sonoma County, California

(38°20.8'N; 123°04.5'W). It was about 0930 hours and the water was cold

and very clear.Vogensen was wearing dark blue swimming trunks.  Pat DuNah, age 18, was bitten by a shark on Saturday, 5 August 1978, while swimming 30 meters from shore off Pajaro Dunes Beach, near Santa Cruz, California (36°51.6'N; 121°48.6'W). DuNah and two companion swimmers had decided to go body surfing. They swam out some 100 meters from the beach at about 1200 hours. The sky was overcast and the air warm, about 20°C, with a mild wind generating small ocean groundswells, creating water visibility of 3 to 5 meters.

Pat DuNah, age 18, was bitten by a shark on Saturday, 5 August 1978, while swimming 30 meters from shore off Pajaro Dunes Beach, near Santa Cruz, California (36°51.6'N; 121°48.6'W). DuNah and two companion swimmers had decided to go body surfing. They swam out some 100 meters from the beach at about 1200 hours. The sky was overcast and the air warm, about 20°C, with a mild wind generating small ocean groundswells, creating water visibility of 3 to 5 meters.

The

knowledge that female victims were only a small percentage of the

shark-attack cases reported in the ISAF by the end of the 1950s would

undoubtedly have been of little comfort to Susan Marie Theriot, age

16, on Thursday, 19 May 1960. On this day, Theriot became the first

known female to be attacked by a shark off the Pacific Coast in the

Twentieth Century. The attack occurred while she was swimming with

four student friends at Hidden Beach, near Aptos and Santa Cruz, in

Santa Cruz County, California (36°57.6'N; 121°53.7'W). It

was 1300 hours as Theriot and her companions were joined by 38 other

sophomores from Mora Central High School for a day of fun at the beach.

The beach outing was a reward for selling a specified number of their

high school yearbooks. Witnesses said Theriot was 40 to 50 meters from

shore in water 1 to 2 fathoms deep with a sandy bottom.

The

knowledge that female victims were only a small percentage of the

shark-attack cases reported in the ISAF by the end of the 1950s would

undoubtedly have been of little comfort to Susan Marie Theriot, age

16, on Thursday, 19 May 1960. On this day, Theriot became the first

known female to be attacked by a shark off the Pacific Coast in the

Twentieth Century. The attack occurred while she was swimming with

four student friends at Hidden Beach, near Aptos and Santa Cruz, in

Santa Cruz County, California (36°57.6'N; 121°53.7'W). It

was 1300 hours as Theriot and her companions were joined by 38 other

sophomores from Mora Central High School for a day of fun at the beach.

The beach outing was a reward for selling a specified number of their

high school yearbooks. Witnesses said Theriot was 40 to 50 meters from

shore in water 1 to 2 fathoms deep with a sandy bottom.  On Monday, 17 September 1984, at 1530 hours, Brian Cramer would be injured while

swimming at Mission Beach, a community in San Diego, California (32 47.1'

N; 11715.4'W). This was yet another instance where the identity of the attacking shark could

not be determined. Cramer was wading in waist-deep water when he felt something grab his

right arm near the elbow and violently shake it. A crescent-shaped wound, composed

of five individual tooth punctures, required many sutures for closure. The wound was 7.5 to

10 centimeters in diameter. The swimmer reported being in a school of baitfish when attacked. Cramer

said he could not see what had struck him because “the water was too murky to see anything

clearly.” Several biologists believed the attacker to be a small requiem

shark (Carcharhinidae). James Stewart, of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography,

considered a small Blue Shark (Prionace glauca) the most likely suspect, as “they

are frequently seen close inshore chasing baitfish.”Cramer’s injury was

minor, and physicians expected a complete recovery for the swimmer. Overnight

hospitalization was not required.

On Monday, 17 September 1984, at 1530 hours, Brian Cramer would be injured while

swimming at Mission Beach, a community in San Diego, California (32 47.1'

N; 11715.4'W). This was yet another instance where the identity of the attacking shark could

not be determined. Cramer was wading in waist-deep water when he felt something grab his

right arm near the elbow and violently shake it. A crescent-shaped wound, composed

of five individual tooth punctures, required many sutures for closure. The wound was 7.5 to

10 centimeters in diameter. The swimmer reported being in a school of baitfish when attacked. Cramer

said he could not see what had struck him because “the water was too murky to see anything

clearly.” Several biologists believed the attacker to be a small requiem

shark (Carcharhinidae). James Stewart, of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography,

considered a small Blue Shark (Prionace glauca) the most likely suspect, as “they

are frequently seen close inshore chasing baitfish.”Cramer’s injury was

minor, and physicians expected a complete recovery for the swimmer. Overnight

hospitalization was not required. On Sunday, 28 April 1957, shock and

disbelief would grip one of California's small coastal communities. Peter

Savino, age 25, of Brooklyn, New York, would lose his life while swimming

with fellow California Polytechnic Institute student Daniel Hogan, age 22,

about 3 kilometers north of Morro Rock at 35th Street, Atascadero Beach, San Luis

Obispo County (35°24.2'N; 120°52.5'W). Savino and Hogan were accompanied

by 10 to 12 other student acquaintances for an early-afternoon ocean swim.

It was about 1330 hours on what was described by one companion as "a

very warm, sunny day."

On Sunday, 28 April 1957, shock and

disbelief would grip one of California's small coastal communities. Peter

Savino, age 25, of Brooklyn, New York, would lose his life while swimming

with fellow California Polytechnic Institute student Daniel Hogan, age 22,

about 3 kilometers north of Morro Rock at 35th Street, Atascadero Beach, San Luis

Obispo County (35°24.2'N; 120°52.5'W). Savino and Hogan were accompanied

by 10 to 12 other student acquaintances for an early-afternoon ocean swim.

It was about 1330 hours on what was described by one companion as "a

very warm, sunny day." Knight was positive that the shark

observed was not a Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus), as was

reported in several newspaper accounts of the attack. Knight also reported

sighting several smaller Blue Sharks in the search area. The search resumed the

following day, but was unsuccessful. Savino's body was never recovered.

Knight was positive that the shark

observed was not a Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus), as was

reported in several newspaper accounts of the attack. Knight also reported

sighting several smaller Blue Sharks in the search area. The search resumed the

following day, but was unsuccessful. Savino's body was never recovered.