| |

Pacific Coast Shark Attack Statistics

The total number (108) of authenticated cases of shark attack reported

from the Pacific Coast of North America during the Twentieth Century

is insufficient to determine the probability, or odds, of encountering

a shark when entering these waters. During the first half of the Twentieth

Century only one authenticated unprovoked shark attack was reported

from the Pacific Coast, with the remaining 107 cases occurring during

the last half of this 100-year period. The total number of reported

shark attacks speaks volumes about the rarity of these events, when

compared to the almost astronomical number of potential victims that

entered the waters of the Pacific Coast during the Twentieth Century.

Due to the extremely low number of attacks being analyzed in this

study, the ramifications — if any — of the data presented

here are considered with a healthy measure of caution and common sense.

Attack Documentation Sources

In

his analysis of the ISAF, Baldridge noted, “It was sobering

to find that 89.9% of the files on human shark attack held in the

ISAF, accounts of what happened were based primarily upon information

supplied by persons who were neither the objects of the attacks nor

were they even there at the time to actually see what happened. To

be completely realistic, therefore, it must be conceded that the ISAF

is made up largely of hearsay evidence, mostly documented long after

the event happened.” In

his analysis of the ISAF, Baldridge noted, “It was sobering

to find that 89.9% of the files on human shark attack held in the

ISAF, accounts of what happened were based primarily upon information

supplied by persons who were neither the objects of the attacks nor

were they even there at the time to actually see what happened. To

be completely realistic, therefore, it must be conceded that the ISAF

is made up largely of hearsay evidence, mostly documented long after

the event happened.”

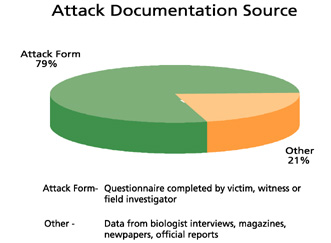

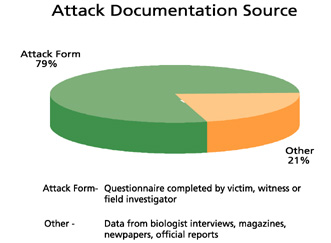

In contrast to the ISAF analysis, primary data for 84 (78%) of the

108 cases included in this study were obtained from Shark Research

Committee questionnaires that were completed either by the victim,

rescuers, witnesses, or qualified field investigators. The remaining

24 (22%) cases derived their data from either ISAF case histories,

published and unpublished accounts by research biologists, medical

records, local or federal government agency reports, or newspaper

and/or magazine articles.

Thus, unlike the ISAF data, the vast majority of information about

shark attacks included in the present study was supplied by people

who were actually there. Due to the sustained effort to collect this

information, it is hoped that the resulting data are at least somewhat

more accurate than the “largely hearsay” data

reported by Baldridge.

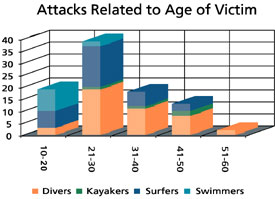

Attacks Related to Age of Victim

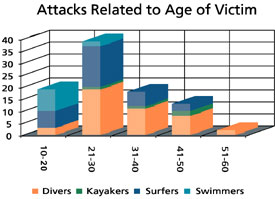

The

median age of Pacific Coast residents was not available for the present

study. However, the average age for all victims included in this study

is 29 years. Victim age was available for 91 (84%) of the 108 cases

considered in this study. The average age (in years) of each victim

group breaks down as follows: swimmers 18, surfers 27, divers 33,

and kayakers 37. Note that the average age of victims in each group

reflects the average age of participants in each group - there are

plenty of teenagers who splash about at the beach but very few 50-year-old

surfers, a fact that is reflected by the data. The

median age of Pacific Coast residents was not available for the present

study. However, the average age for all victims included in this study

is 29 years. Victim age was available for 91 (84%) of the 108 cases

considered in this study. The average age (in years) of each victim

group breaks down as follows: swimmers 18, surfers 27, divers 33,

and kayakers 37. Note that the average age of victims in each group

reflects the average age of participants in each group - there are

plenty of teenagers who splash about at the beach but very few 50-year-old

surfers, a fact that is reflected by the data.

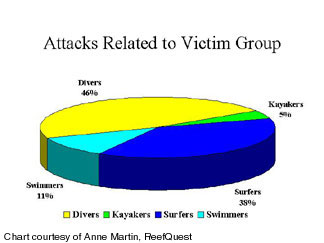

Attacks Related To Victim Groups

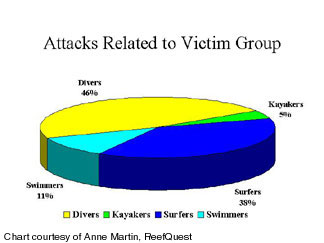

Because of the divergent activities required of surfing, diving, kayaking,

and swimming, it was necessary to define the victim groups into which

each of the 108 authenticated shark attacks reported in this study

would be placed. Definitions of the water activities required for

inclusion in the swimmer victim group were: swimming and body surfing

(when the participant did not use a board). Those in the surfer victim

group included: surfboarders, body boarders, boogie boarders, paddle

boarders, and wind surfers. The diver victim group included: commercial

(hookah), scuba, and free diving. There was no authenticated case

of a shark attack against a hard-hat diver along the Pacific Coast

during the entire Twentieth Century. The kayaker victim group is composed

of those utilizing a kayak or similar oceangoing vessel. To this writing,

Jet Skis had not been struck by, or encountered, a White Shark. However,

a review of the above ocean sport activities would suggest that Jet

Skis will most likely become the next victim group sometime, early

on, in the Twenty-First Century. The distribution of the 108 authenticated

unprovoked shark attacks from the Pacific Coast among these victim

groups is: divers, 50 (46%); surfers, 41 (38%); swimmers, 12 (11%);

and kayakers, 5 (5%).

Because of the divergent activities required of surfing, diving, kayaking,

and swimming, it was necessary to define the victim groups into which

each of the 108 authenticated shark attacks reported in this study

would be placed. Definitions of the water activities required for

inclusion in the swimmer victim group were: swimming and body surfing

(when the participant did not use a board). Those in the surfer victim

group included: surfboarders, body boarders, boogie boarders, paddle

boarders, and wind surfers. The diver victim group included: commercial

(hookah), scuba, and free diving. There was no authenticated case

of a shark attack against a hard-hat diver along the Pacific Coast

during the entire Twentieth Century. The kayaker victim group is composed

of those utilizing a kayak or similar oceangoing vessel. To this writing,

Jet Skis had not been struck by, or encountered, a White Shark. However,

a review of the above ocean sport activities would suggest that Jet

Skis will most likely become the next victim group sometime, early

on, in the Twenty-First Century. The distribution of the 108 authenticated

unprovoked shark attacks from the Pacific Coast among these victim

groups is: divers, 50 (46%); surfers, 41 (38%); swimmers, 12 (11%);

and kayakers, 5 (5%).

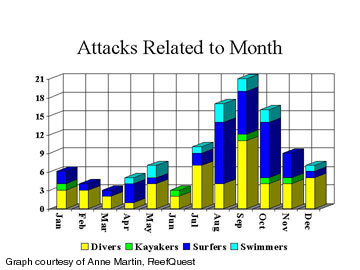

Attacks Related To Month

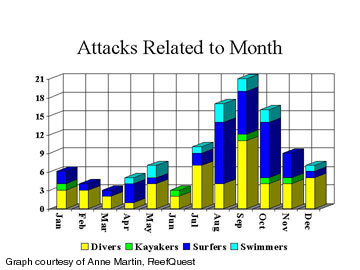

Along

the Pacific Coast of North America, shark attacks on humans occurred

in every month of the year, with a dramatic peak during August, September

and October. The fewest attacks reported for a month were three each

for March and June. There were four shark attacks reported in February

and five for April. January had six confirmed attacks, with May and

December reporting seven cases each. There were nine cases authenticated

for November, with 10 incidents occurring during July. These nine

months accounted for 54 (50%) of the 108 confirmed shark attacks from

the Pacific Coast. The remaining 54 (50%) shark-attack cases were:

16 reported in October, 17 in August, and 21 in September. Along

the Pacific Coast of North America, shark attacks on humans occurred

in every month of the year, with a dramatic peak during August, September

and October. The fewest attacks reported for a month were three each

for March and June. There were four shark attacks reported in February

and five for April. January had six confirmed attacks, with May and

December reporting seven cases each. There were nine cases authenticated

for November, with 10 incidents occurring during July. These nine

months accounted for 54 (50%) of the 108 confirmed shark attacks from

the Pacific Coast. The remaining 54 (50%) shark-attack cases were:

16 reported in October, 17 in August, and 21 in September.

During these three "peak months," 19 divers and 26 surfers

were attacked, representing 38% and 63% of the total number of attacks

for their respective groups. Current data on diving usage along the

Pacific Coast were not available, however, diving is most pleasant

from midsummer until late fall, after which winter storms severely

reduce underwater visibility due to plankton blooms and increased

turbidity from river run-off. At such times, only the most ardent

sport divers and commercial divers are found in the water. In the

case of surfers they prefer those areas in and around river mouths

because of their gently sloping, sandy bottoms, which generate the

large, predictable waves that produce the longest and most satisfying

rides. There appears to be a strong correlation between the time of

year that anadromous fishes (such as Pacific salmon and Steelhead,

of the family Salmonidae) congregate at river mouths in preparation

for their annual spawning runs and the incidence of White Shark attacks

on surfers, divers, kayakers, and swimmers at or near these locations.

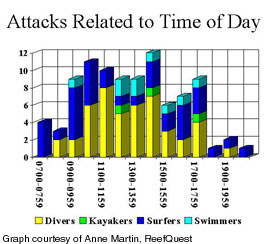

Attacks Related To Time of Day

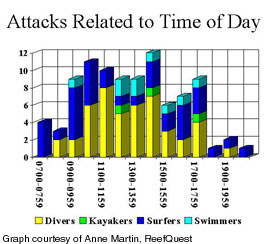

Pacific

Coast shark attacks occurred during all daylight hours. They were

relatively constant between 0900 and 1800 hours and did not occur between

2015 and 0719 hours. The hours during which no attacks were recorded

correspond roughly to the period between sunset and daybreak, with

the early morning and late evening extremes involving surfers. Most

swimmers heed traditional advice and do not enter the ocean before

dawn or after sunset. Unlike divers and kayakers, surfers can engage

in their sport within minutes of arriving at the beach. Further, unlike

divers, surfers are not dependent on ambient light levels to engage

in their sport, relying on kinesthetic cues (the feel of their boards'

reactions) rather than visual ones. Therefore, surfers can extend

their use of the ocean both earlier and later than can swimmers or

divers. Pacific

Coast shark attacks occurred during all daylight hours. They were

relatively constant between 0900 and 1800 hours and did not occur between

2015 and 0719 hours. The hours during which no attacks were recorded

correspond roughly to the period between sunset and daybreak, with

the early morning and late evening extremes involving surfers. Most

swimmers heed traditional advice and do not enter the ocean before

dawn or after sunset. Unlike divers and kayakers, surfers can engage

in their sport within minutes of arriving at the beach. Further, unlike

divers, surfers are not dependent on ambient light levels to engage

in their sport, relying on kinesthetic cues (the feel of their boards'

reactions) rather than visual ones. Therefore, surfers can extend

their use of the ocean both earlier and later than can swimmers or

divers.

With only five cases involving kayakers, it is impossible to draw

any firm conclusions about the temporal patterns of ocean use by this

victim group. However, due to the amount of water covered (frequently

20 kilometers or more), kayakers present themselves over a wider area

than do surfers — who typically stay within the area chosen —

or sport divers, whose range is limited by their air supply. Like

surfers, kayakers are not greatly affected by ocean water temperature

and thus can paddle for extended periods. With the increasing popularity

of ocean kayaking clubs and the growing trend toward "moonlight" excursions

— reminiscent of horseback riding under the stars — an attack

by a White Shark against a kayak after sunset would seem to be only

a matter of time.

In any case, temporal patterns of shark attacks along the Pacific

Coast during the Twentieth Century probably reflect the strong diurnal

bias of human activity rather than that of sharks.

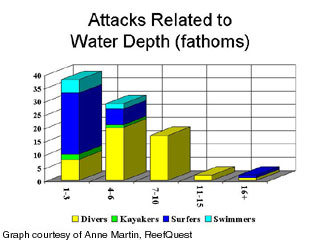

Attacks Related to Water Depth

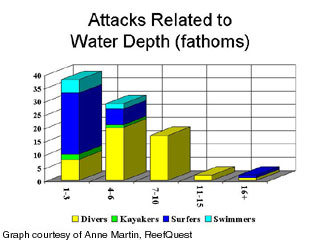

Of

the 108 authenticated cases of shark attack occurring along the Pacific

Coast during the Twentieth Century, data on water depth were available

for 88 (82%) cases. Of these 88 cases, 30 (34%) were directed at surfers,

while 48 (55%) were against divers. The predominance of depth data

reported by divers reflects the fact that accurate depth gauges are

a standard part of diving equipment. Of the 30 reported attacks against

surfers, 23 (77%) occurred where the water depth was 1 to 3 fm. Of

the 48 reported attacks on divers, 37 (77%) occurred where the water

depth was between 4 and 10 fm, with 20 of the 37 (54%) occurring where

the depth was 4 to 6 fm. Attacks against surfers occurred over relatively

shallow, near-shore waters that are conducive to surf riding. Attacks

against divers occurred in or over somewhat deeper water, but within

the limits of diver safety and comfort. Therefore, once again, these

data probably reflect the demands of the chosen ocean sport and/or

human preferences for ocean usage, rather than the depth preferences

of attacking sharks. Of

the 108 authenticated cases of shark attack occurring along the Pacific

Coast during the Twentieth Century, data on water depth were available

for 88 (82%) cases. Of these 88 cases, 30 (34%) were directed at surfers,

while 48 (55%) were against divers. The predominance of depth data

reported by divers reflects the fact that accurate depth gauges are

a standard part of diving equipment. Of the 30 reported attacks against

surfers, 23 (77%) occurred where the water depth was 1 to 3 fm. Of

the 48 reported attacks on divers, 37 (77%) occurred where the water

depth was between 4 and 10 fm, with 20 of the 37 (54%) occurring where

the depth was 4 to 6 fm. Attacks against surfers occurred over relatively

shallow, near-shore waters that are conducive to surf riding. Attacks

against divers occurred in or over somewhat deeper water, but within

the limits of diver safety and comfort. Therefore, once again, these

data probably reflect the demands of the chosen ocean sport and/or

human preferences for ocean usage, rather than the depth preferences

of attacking sharks.

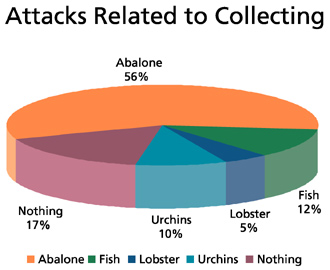

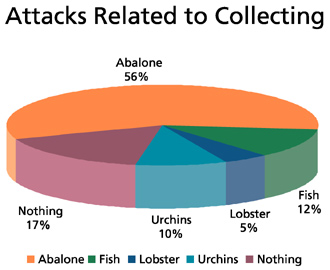

Attacks Related to Collecting of Marine Organisms

In

the ISAF analysis Baldridge determined that "of 103 free

divers where judgement was possible, 80% were engaged in spearfishing.

It was possible to conclude in 72 cases that 51% of the free-diver

victims had captive fish in their possession at the times that they

were attacked. SCUBA divers showed a lower incidence of spearfishing;

53% of 19 cases, with almost all of them (50% of 18 cases) possessing

captured fish. These data appeared to severely indict spearfishing

as a provocative act leading possibly to shark attack. Logic supports

this conclusion. However, it cannot be statistically validated in

the absence of corresponding data on diver non-victims." In

the ISAF analysis Baldridge determined that "of 103 free

divers where judgement was possible, 80% were engaged in spearfishing.

It was possible to conclude in 72 cases that 51% of the free-diver

victims had captive fish in their possession at the times that they

were attacked. SCUBA divers showed a lower incidence of spearfishing;

53% of 19 cases, with almost all of them (50% of 18 cases) possessing

captured fish. These data appeared to severely indict spearfishing

as a provocative act leading possibly to shark attack. Logic supports

this conclusion. However, it cannot be statistically validated in

the absence of corresponding data on diver non-victims."

Of the 108 cases included in the present study, 50 (47%) were hunting

or collecting marine organisms. All 50 of them belong to the diver

victim group, of which 24 (56%) were collecting abalone, 12 (29%)

were spearfishing, four (10%) were commercial urchin divers, and two

(5%) were hunting lobster. It is intriguing that no divers whose efforts

were dedicated to underwater photography along the Pacific Coast were

bitten by sharks during the entire Twentieth Century. This may be

because underwater photographers are generally fine and observant

marine naturalists, keenly aware of what is happening in the environment

around them. In contrast, divers concentrating on hunting and capturing

marine organisms often focus on their purpose to the exclusion of

all else. This degree of concentration may render diving hunters vulnerable

to attack by sharks.

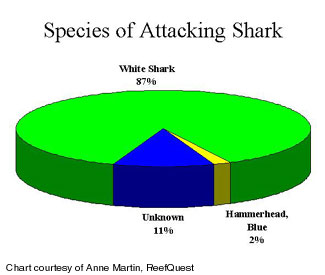

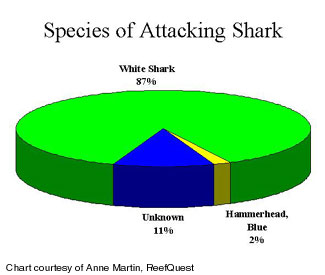

Species of Attacking Shark

In

H. David Baldridge's 1973 published analysis of the International

Shark Attack File, he determined the following: "At least some

level of identification of the attacker was possible in 267 cases.

As popular belief would have it, the great white shark (Carcharodon

carcharias) was cited most often, with 32 [12%] known attacks

to its discredit." This global ISAF result pales in comparison

to that of this regional study of attacks from the Pacific Coast of

North America.. Of the 108 authenticated cases of shark attack reported

during the Twentieth Century, 12 (11%) were unidentified, one (1%)

was attributable to the Blue Shark, and one (1%) to the Common Hammerhead.

In the remaining 94 cases (87%) the White Shark was either positively

identified or highly suspect as the species responsible for the attack.

Distribution of these 94 cases among victim groups is as follows:

six swimmers (7%), 45 divers (48%), 39 surfers (41%) and four kayakers

(4%). Therefore, in the unlikely event that you are attacked by a

shark off the Pacific Coast of North America, the odds are 9 to 1

that it will be a White Shark. With the close of the Twentieth Century,

it is estimated that more than 60% of all recorded White Shark attacks

worldwide had occurred off the Pacific Coast of North America. In

H. David Baldridge's 1973 published analysis of the International

Shark Attack File, he determined the following: "At least some

level of identification of the attacker was possible in 267 cases.

As popular belief would have it, the great white shark (Carcharodon

carcharias) was cited most often, with 32 [12%] known attacks

to its discredit." This global ISAF result pales in comparison

to that of this regional study of attacks from the Pacific Coast of

North America.. Of the 108 authenticated cases of shark attack reported

during the Twentieth Century, 12 (11%) were unidentified, one (1%)

was attributable to the Blue Shark, and one (1%) to the Common Hammerhead.

In the remaining 94 cases (87%) the White Shark was either positively

identified or highly suspect as the species responsible for the attack.

Distribution of these 94 cases among victim groups is as follows:

six swimmers (7%), 45 divers (48%), 39 surfers (41%) and four kayakers

(4%). Therefore, in the unlikely event that you are attacked by a

shark off the Pacific Coast of North America, the odds are 9 to 1

that it will be a White Shark. With the close of the Twentieth Century,

it is estimated that more than 60% of all recorded White Shark attacks

worldwide had occurred off the Pacific Coast of North America.

|

In

his analysis of the ISAF, Baldridge noted, “It was sobering

to find that 89.9% of the files on human shark attack held in the

ISAF, accounts of what happened were based primarily upon information

supplied by persons who were neither the objects of the attacks nor

were they even there at the time to actually see what happened. To

be completely realistic, therefore, it must be conceded that the ISAF

is made up largely of hearsay evidence, mostly documented long after

the event happened.”

In

his analysis of the ISAF, Baldridge noted, “It was sobering

to find that 89.9% of the files on human shark attack held in the

ISAF, accounts of what happened were based primarily upon information

supplied by persons who were neither the objects of the attacks nor

were they even there at the time to actually see what happened. To

be completely realistic, therefore, it must be conceded that the ISAF

is made up largely of hearsay evidence, mostly documented long after

the event happened.” The

median age of Pacific Coast residents was not available for the present

study. However, the average age for all victims included in this study

is 29 years. Victim age was available for 91 (84%) of the 108 cases

considered in this study. The average age (in years) of each victim

group breaks down as follows: swimmers 18, surfers 27, divers 33,

and kayakers 37. Note that the average age of victims in each group

reflects the average age of participants in each group - there are

plenty of teenagers who splash about at the beach but very few 50-year-old

surfers, a fact that is reflected by the data.

The

median age of Pacific Coast residents was not available for the present

study. However, the average age for all victims included in this study

is 29 years. Victim age was available for 91 (84%) of the 108 cases

considered in this study. The average age (in years) of each victim

group breaks down as follows: swimmers 18, surfers 27, divers 33,

and kayakers 37. Note that the average age of victims in each group

reflects the average age of participants in each group - there are

plenty of teenagers who splash about at the beach but very few 50-year-old

surfers, a fact that is reflected by the data. Because of the divergent activities required of surfing, diving, kayaking,

and swimming, it was necessary to define the victim groups into which

each of the 108 authenticated shark attacks reported in this study

would be placed. Definitions of the water activities required for

inclusion in the swimmer victim group were: swimming and body surfing

(when the participant did not use a board). Those in the surfer victim

group included: surfboarders, body boarders, boogie boarders, paddle

boarders, and wind surfers. The diver victim group included: commercial

(hookah), scuba, and free diving. There was no authenticated case

of a shark attack against a hard-hat diver along the Pacific Coast

during the entire Twentieth Century. The kayaker victim group is composed

of those utilizing a kayak or similar oceangoing vessel. To this writing,

Jet Skis had not been struck by, or encountered, a White Shark. However,

a review of the above ocean sport activities would suggest that Jet

Skis will most likely become the next victim group sometime, early

on, in the Twenty-First Century. The distribution of the 108 authenticated

unprovoked shark attacks from the Pacific Coast among these victim

groups is: divers, 50 (46%); surfers, 41 (38%); swimmers, 12 (11%);

and kayakers, 5 (5%).

Because of the divergent activities required of surfing, diving, kayaking,

and swimming, it was necessary to define the victim groups into which

each of the 108 authenticated shark attacks reported in this study

would be placed. Definitions of the water activities required for

inclusion in the swimmer victim group were: swimming and body surfing

(when the participant did not use a board). Those in the surfer victim

group included: surfboarders, body boarders, boogie boarders, paddle

boarders, and wind surfers. The diver victim group included: commercial

(hookah), scuba, and free diving. There was no authenticated case

of a shark attack against a hard-hat diver along the Pacific Coast

during the entire Twentieth Century. The kayaker victim group is composed

of those utilizing a kayak or similar oceangoing vessel. To this writing,

Jet Skis had not been struck by, or encountered, a White Shark. However,

a review of the above ocean sport activities would suggest that Jet

Skis will most likely become the next victim group sometime, early

on, in the Twenty-First Century. The distribution of the 108 authenticated

unprovoked shark attacks from the Pacific Coast among these victim

groups is: divers, 50 (46%); surfers, 41 (38%); swimmers, 12 (11%);

and kayakers, 5 (5%).  Along

the Pacific Coast of North America, shark attacks on humans occurred

in every month of the year, with a dramatic peak during August, September

and October. The fewest attacks reported for a month were three each

for March and June. There were four shark attacks reported in February

and five for April. January had six confirmed attacks, with May and

December reporting seven cases each. There were nine cases authenticated

for November, with 10 incidents occurring during July. These nine

months accounted for 54 (50%) of the 108 confirmed shark attacks from

the Pacific Coast. The remaining 54 (50%) shark-attack cases were:

16 reported in October, 17 in August, and 21 in September.

Along

the Pacific Coast of North America, shark attacks on humans occurred

in every month of the year, with a dramatic peak during August, September

and October. The fewest attacks reported for a month were three each

for March and June. There were four shark attacks reported in February

and five for April. January had six confirmed attacks, with May and

December reporting seven cases each. There were nine cases authenticated

for November, with 10 incidents occurring during July. These nine

months accounted for 54 (50%) of the 108 confirmed shark attacks from

the Pacific Coast. The remaining 54 (50%) shark-attack cases were:

16 reported in October, 17 in August, and 21 in September. Pacific

Coast shark attacks occurred during all daylight hours. They were

relatively constant between 0900 and 1800 hours and did not occur between

2015 and 0719 hours. The hours during which no attacks were recorded

correspond roughly to the period between sunset and daybreak, with

the early morning and late evening extremes involving surfers. Most

swimmers heed traditional advice and do not enter the ocean before

dawn or after sunset. Unlike divers and kayakers, surfers can engage

in their sport within minutes of arriving at the beach. Further, unlike

divers, surfers are not dependent on ambient light levels to engage

in their sport, relying on kinesthetic cues (the feel of their boards'

reactions) rather than visual ones. Therefore, surfers can extend

their use of the ocean both earlier and later than can swimmers or

divers.

Pacific

Coast shark attacks occurred during all daylight hours. They were

relatively constant between 0900 and 1800 hours and did not occur between

2015 and 0719 hours. The hours during which no attacks were recorded

correspond roughly to the period between sunset and daybreak, with

the early morning and late evening extremes involving surfers. Most

swimmers heed traditional advice and do not enter the ocean before

dawn or after sunset. Unlike divers and kayakers, surfers can engage

in their sport within minutes of arriving at the beach. Further, unlike

divers, surfers are not dependent on ambient light levels to engage

in their sport, relying on kinesthetic cues (the feel of their boards'

reactions) rather than visual ones. Therefore, surfers can extend

their use of the ocean both earlier and later than can swimmers or

divers.  Of

the 108 authenticated cases of shark attack occurring along the Pacific

Coast during the Twentieth Century, data on water depth were available

for 88 (82%) cases. Of these 88 cases, 30 (34%) were directed at surfers,

while 48 (55%) were against divers. The predominance of depth data

reported by divers reflects the fact that accurate depth gauges are

a standard part of diving equipment. Of the 30 reported attacks against

surfers, 23 (77%) occurred where the water depth was 1 to 3 fm. Of

the 48 reported attacks on divers, 37 (77%) occurred where the water

depth was between 4 and 10 fm, with 20 of the 37 (54%) occurring where

the depth was 4 to 6 fm. Attacks against surfers occurred over relatively

shallow, near-shore waters that are conducive to surf riding. Attacks

against divers occurred in or over somewhat deeper water, but within

the limits of diver safety and comfort. Therefore, once again, these

data probably reflect the demands of the chosen ocean sport and/or

human preferences for ocean usage, rather than the depth preferences

of attacking sharks.

Of

the 108 authenticated cases of shark attack occurring along the Pacific

Coast during the Twentieth Century, data on water depth were available

for 88 (82%) cases. Of these 88 cases, 30 (34%) were directed at surfers,

while 48 (55%) were against divers. The predominance of depth data

reported by divers reflects the fact that accurate depth gauges are

a standard part of diving equipment. Of the 30 reported attacks against

surfers, 23 (77%) occurred where the water depth was 1 to 3 fm. Of

the 48 reported attacks on divers, 37 (77%) occurred where the water

depth was between 4 and 10 fm, with 20 of the 37 (54%) occurring where

the depth was 4 to 6 fm. Attacks against surfers occurred over relatively

shallow, near-shore waters that are conducive to surf riding. Attacks

against divers occurred in or over somewhat deeper water, but within

the limits of diver safety and comfort. Therefore, once again, these

data probably reflect the demands of the chosen ocean sport and/or

human preferences for ocean usage, rather than the depth preferences

of attacking sharks.  In

the ISAF analysis Baldridge determined that "of 103 free

divers where judgement was possible, 80% were engaged in spearfishing.

It was possible to conclude in 72 cases that 51% of the free-diver

victims had captive fish in their possession at the times that they

were attacked. SCUBA divers showed a lower incidence of spearfishing;

53% of 19 cases, with almost all of them (50% of 18 cases) possessing

captured fish. These data appeared to severely indict spearfishing

as a provocative act leading possibly to shark attack. Logic supports

this conclusion. However, it cannot be statistically validated in

the absence of corresponding data on diver non-victims."

In

the ISAF analysis Baldridge determined that "of 103 free

divers where judgement was possible, 80% were engaged in spearfishing.

It was possible to conclude in 72 cases that 51% of the free-diver

victims had captive fish in their possession at the times that they

were attacked. SCUBA divers showed a lower incidence of spearfishing;

53% of 19 cases, with almost all of them (50% of 18 cases) possessing

captured fish. These data appeared to severely indict spearfishing

as a provocative act leading possibly to shark attack. Logic supports

this conclusion. However, it cannot be statistically validated in

the absence of corresponding data on diver non-victims." In

H. David Baldridge's 1973 published analysis of the International

Shark Attack File, he determined the following: "At least some

level of identification of the attacker was possible in 267 cases.

As popular belief would have it, the great white shark (Carcharodon

carcharias) was cited most often, with 32 [12%] known attacks

to its discredit." This global ISAF result pales in comparison

to that of this regional study of attacks from the Pacific Coast of

North America.. Of the 108 authenticated cases of shark attack reported

during the Twentieth Century, 12 (11%) were unidentified, one (1%)

was attributable to the Blue Shark, and one (1%) to the Common Hammerhead.

In the remaining 94 cases (87%) the White Shark was either positively

identified or highly suspect as the species responsible for the attack.

Distribution of these 94 cases among victim groups is as follows:

six swimmers (7%), 45 divers (48%), 39 surfers (41%) and four kayakers

(4%). Therefore, in the unlikely event that you are attacked by a

shark off the Pacific Coast of North America, the odds are 9 to 1

that it will be a White Shark. With the close of the Twentieth Century,

it is estimated that more than 60% of all recorded White Shark attacks

worldwide had occurred off the Pacific Coast of North America.

In

H. David Baldridge's 1973 published analysis of the International

Shark Attack File, he determined the following: "At least some

level of identification of the attacker was possible in 267 cases.

As popular belief would have it, the great white shark (Carcharodon

carcharias) was cited most often, with 32 [12%] known attacks

to its discredit." This global ISAF result pales in comparison

to that of this regional study of attacks from the Pacific Coast of

North America.. Of the 108 authenticated cases of shark attack reported

during the Twentieth Century, 12 (11%) were unidentified, one (1%)

was attributable to the Blue Shark, and one (1%) to the Common Hammerhead.

In the remaining 94 cases (87%) the White Shark was either positively

identified or highly suspect as the species responsible for the attack.

Distribution of these 94 cases among victim groups is as follows:

six swimmers (7%), 45 divers (48%), 39 surfers (41%) and four kayakers

(4%). Therefore, in the unlikely event that you are attacked by a

shark off the Pacific Coast of North America, the odds are 9 to 1

that it will be a White Shark. With the close of the Twentieth Century,

it is estimated that more than 60% of all recorded White Shark attacks

worldwide had occurred off the Pacific Coast of North America.