| |

Unprovoked White Shark Attacks on Surfers

There were 41 confirmed unprovoked shark attacks on surfers along

the West Coast of North America during the Twentieth Century, which

represented 38% of the total reported cases. The White Shark

was determined to be the causal species in all but two. It

has been suggested that White Shark attacks on surfers are the result

of the attacking shark mistakenly identifying the surfer for a pinniped.

Predatory attacks by White Sharks on pinnipeds have been described

from numerous locations worldwide, including the Farallon Islands,

San Francisco, California. The attacks on Mike Shook and Craig

Rogers cast a shadow of doubt as to whether all White Shark attacks

on surfers are the result of "mistaken identity." For

example; Why would a White Shark continue to strike an object it had

determined to be inedible following its first bite? Also, are White

Shark predatory attacks so gentle that the prey doesn't know it

has been captured? Sometimes the amount of effort expended to determine

the motivation for an attack clouds the most important aspect of

the case in question — was a shark responsible?

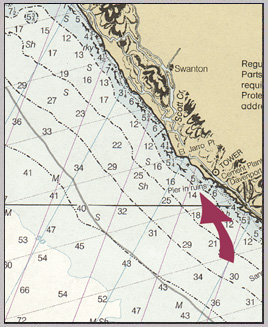

The first authenticated White Shark attack on a wind surfer off

the Pacific Coast of North America occurred on Thursday, 28 September

1995. Michael J. Sullivan, age 25, was attacked about 1 km off Davenport

Landing, about 24 km north of Santa Cruz, California (37°00.2’N:

122°12.3’W). His black wetsuit had purple accents, and

his 2.8-m sailboard was lime green with a clear Mylar sail and trimmed

with a red and black margin.

The first authenticated White Shark attack on a wind surfer off

the Pacific Coast of North America occurred on Thursday, 28 September

1995. Michael J. Sullivan, age 25, was attacked about 1 km off Davenport

Landing, about 24 km north of Santa Cruz, California (37°00.2’N:

122°12.3’W). His black wetsuit had purple accents, and

his 2.8-m sailboard was lime green with a clear Mylar sail and trimmed

with a red and black margin.

At 1730 hrs, the sky was clear, the result of a strong 20-knot

wind blowing from the northwest. This wind caused rough water, with

2-to-3-m “wind waves” on the sea surface. No pinnipeds

were seen in the water, although, according to Sullivan, they are

usually in the area. Several dense kelp canopies were 100 m south

and shoreward of the attack location, but there were no kelps in

the immediate area of Sullivan’s attack. This was the fifth

White Shark attack from this recurring location.

Sullivan and about a dozen other wind surfers were near the lower

reef at Davenport Landing, enjoying the excellent sailing conditions.

Sullivan had been sailing about 45 minutes. The wind had begun to

let up, so he turned to head back toward the beach. This maneuver

reduced his forward speed to about 6 knots. There was a light “thump”

to the back of his board as it lifted up underneath him.

Sullivan recalled, “I thought I hit a whale or maybe

a seal. The board coming up out of the water caused me to lose my

balance, and I fell into the water. I had dropped my sail in the

process of falling right on top of the shark’s back. The shark

began slapping its tail wildly, causing the water to be thrown up

in the air, maybe 15 feet [5 m]. I literally crawled off

the shark’s back and swam about 30 feet [10 m] before

I stopped to look back in the direction of my board.”

A wind surfing companion rode toward Sullivan, instructing him

to get back on his board. The water was swirling all around the

board following the shark’s hasty departure. Sullivan swam

to his board, which was upside down and oriented away from the beach.

He righted the board, climbed back on it, and headed for shore.

The fortunate wind surfer’s only injury was an abrasion to

the top of his right foot. Michael J. Sullivan and several who witnessed

the attack thought the White Shark was about 4 m in length.

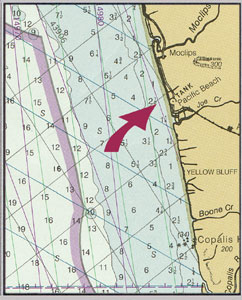

The

first authenticated shark attack for the state of Washington during

the Twentieth Century would occur on Wednesday, 12 April 1989. It

was probably like any other day to surfer Robert Harms as he sat

on his purple surfboard 100 m off Pacific Beach, near Aberdeen in

western Washington (47 12.7'N; 124 12.6'W). McCosker and Lea reported

that Harms, while lying prone on his board at 1045 hrs, felt a sharp

pain in his left arm. The surfer resisted a slight tug on his arm,

instinctively pulling it away from whatever had grabbed it. A large

swirl next to his surfboard drew Harms' attention to a large gray

fish. He gathered himself back onto his board and headed for shore. The

first authenticated shark attack for the state of Washington during

the Twentieth Century would occur on Wednesday, 12 April 1989. It

was probably like any other day to surfer Robert Harms as he sat

on his purple surfboard 100 m off Pacific Beach, near Aberdeen in

western Washington (47 12.7'N; 124 12.6'W). McCosker and Lea reported

that Harms, while lying prone on his board at 1045 hrs, felt a sharp

pain in his left arm. The surfer resisted a slight tug on his arm,

instinctively pulling it away from whatever had grabbed it. A large

swirl next to his surfboard drew Harms' attention to a large gray

fish. He gathered himself back onto his board and headed for shore.

Upon reaching the beach, he removed his wetsuit to treat the multiple

tooth punctures and lacerations. The wounds extended from his thumb

to mid-forearm, a distance of about 25 cm. A companion assisted

Harms in applying antiseptic cleanser and adhesive bandaging to

his wounds. Although somewhat shaken and withdrawn, Harms was not

taken to a medical facility. McCosker and Lea believed this to be

the first and, to date, only White Shark attack on a human to be

authenticated from the state of Washington. I suspect it will not

be the last.

It

is not always possible to determine the species of shark responsible

for an attack. In fact, in a few cases reported during the Twentieth

Century there was a question as to whether a shark was even involved

in the incident. The following case history may be an example of

a shark's being blamed for an attack simply because sharks are known

to attack surfers — a case of "guilt by association." It

is not always possible to determine the species of shark responsible

for an attack. In fact, in a few cases reported during the Twentieth

Century there was a question as to whether a shark was even involved

in the incident. The following case history may be an example of

a shark's being blamed for an attack simply because sharks are known

to attack surfers — a case of "guilt by association."

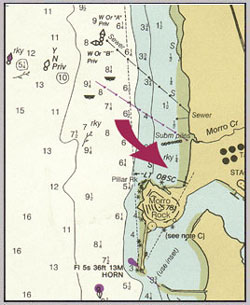

Surfer John Buchanan, age 17, was presumably attacked on Sunday,

29 August 1982, at about 1020 hrs, 100 m north of the recurring

location Morro Rock at Morro Bay, San Luis Obispo County, California

(35 22.5'N; 120 52.0'W).

Buchanan was 50 m south of seven or eight surfers and about 100

m from the beach. Water visibility was 4 to 5 m. Buchanan recalled,

"The water was pretty clean." His board was more than

2 m in length, with a red bottom and sides. He was sitting up on

his board, his feet dangling from either side, when there was a

bump to the left front edge of the surfboard. He glanced down and

saw "the head of an animal, colored gray, with a slight cast

of brown. It looked smooth and somewhat pointed." The surfer

was knocked into the water and began thrashing wildly as he swam

toward the beach, some 75 m away. His surfboard was pulled about

10 m across the surface toward the open sea before it was released.

Buchanan regained his composure and, after abandoning his board,

caught a wave, body surfing to the beach. Unaware of his plight,

a fellow surfer, thinking he had been injured, swam out to retrieve

his board. Fortunately for this "Good Samaritan," the

assailant did not return.

The

surfer did not receive any injuries, although he may have had shattered

nerves. The surfboard was a different story. There were two elongated

impressions, each 5 cm in length, with three smaller punctures and

one large circular indentation. These were the only marks to the

surfboard. Robert N. Lea, California Fish & Game, reported,

"On the day before there had been two shark sightings at

this beach. These could have been blue sharks, basking sharks, or

for that matter any other surface-dwelling shark. The species of

shark that attacked Buchanon's surfboard is unknown." The

surfer did not receive any injuries, although he may have had shattered

nerves. The surfboard was a different story. There were two elongated

impressions, each 5 cm in length, with three smaller punctures and

one large circular indentation. These were the only marks to the

surfboard. Robert N. Lea, California Fish & Game, reported,

"On the day before there had been two shark sightings at

this beach. These could have been blue sharks, basking sharks, or

for that matter any other surface-dwelling shark. The species of

shark that attacked Buchanon's surfboard is unknown."

Following an extensive background investigation into this case,

one additional suspect could be added to the list of possible culprits

- a pinniped. Buchanan's description of his attacker indicated:

"The animal had kind of a pointed head and was colored gray

with a hint of brown." A pinniped's snout is somewhat pointed,

and several species common to the Pacific Coast, including Harbor

Seals (Phoca vitulina richardsi), are colored gray/brown. The pinniped's

predominant whiskers might have been lying flat against its head

- a common behavior when sticking their heads quickly out of water

and playing with or biting objects. They are also known to frequently

harass surfers, including the ramming of their surfboards with such

force that the riders are sometimes knocked into the water. Finally,

Lea reported a circular indentation to the board's bottom.

After examining the dentition of sharks common to the Pacific

Coast, it was determined that none could replicate the damage reported

to the bottom of the surfboard by Lea. Comparisons were made with

the dentition from the following shark species: White (Carcharodon

carcharias), Blue (Prionace glauca), Shortfin Mako (Isurus oxyrinchus),

Sevengill (Notorynchus cepedianus) and Sixgill (Hexanchus griseus)

sharks. None replicated the documented damage sustained to the board.

However, the upper and lower canine teeth of a pinniped typically

produce circular impressions (holes) and have the appropriate spacing

to cause the ridges on the board, as described by Lea. Further,

California Department of Fish & Game spokesman Paul Chappell

was quoted in a local newspaper as saying: "Preliminary

investigation indicates…that the bite was not made by a shark.

The bite pattern does not look like a shark made it. It could have

been just a very playful seal. Harbor Seals are known to frequent

the area where the attack occurred." Ultimately, it was

not possible to determine what species of marine animal was responsible

for the attack on John Buchanan's surfboard.

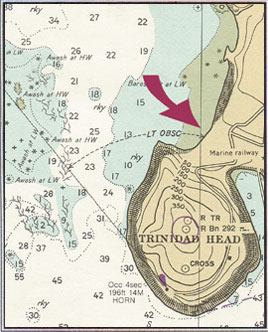

On

Tuesday, 28 August 1990, at 1650 hrs, 22-year-old, Rodney Swan was

attacked while surfing near Trinidad Head, north of Eureka in far

northwestern California (41 03.5'N; On

Tuesday, 28 August 1990, at 1650 hrs, 22-year-old, Rodney Swan was

attacked while surfing near Trinidad Head, north of Eureka in far

northwestern California (41 03.5'N;

124 09.0'W). He was 30 m from shore, adjacent to the north corner

of Trinidad Head. The water was 1 to 2 fm deep, with a temperature

of 14 C and visibility of 2 to 3 m. The sky was overcast, with an

air temperature of about 18 C and a northerly breeze causing a light

chop across the small groundswells. The ocean floor was sandy with

a few scattered sandbars and no visible kelp canopies present in

the immediate area. Several pinnipeds basked on nearby rocks and

barked from time to time, but displayed no unusual behavior. Swan

sat on his 2-m orange and white surfboard just off a rocky headland

where several pinnipeds were basking near the water's edge; no pinnipeds

were observed in the water. The waves were forming poorly for surfing

purposes, causing several of Swan's companions to go ashore in frustration.

Swan was dressed in a full black wetsuit.

The

quiet of late afternoon was shattered suddenly by the sound of a

tremendous impact. A White Shark struck Swan's surfboard with such

force that the wind was knocked out of him as he was catapulted

1 to 2 m into the air before plunging into the water. Opening his

eyes underwater, he saw the flank of a large White Shark less than

1 m away. The shark was barely visible through the foaming, bubbling

water. The shark appeared to be 5 to 6 m in length, with a very

large girth. The

quiet of late afternoon was shattered suddenly by the sound of a

tremendous impact. A White Shark struck Swan's surfboard with such

force that the wind was knocked out of him as he was catapulted

1 to 2 m into the air before plunging into the water. Opening his

eyes underwater, he saw the flank of a large White Shark less than

1 m away. The shark was barely visible through the foaming, bubbling

water. The shark appeared to be 5 to 6 m in length, with a very

large girth.

Swan recalled, "My heart was just about to rip through

my rib cage. The shark must have felt it, because it was so close

to me I wanted to touch it. I really wanted to touch it. I thought,

if you're going to take my life, I at least want to touch you. I

surfaced in the churning, bubbling water and just floated, numb

and winded, waiting for the shark to finish me off. As I floated

on the surface trying to catch my breath, I said several prayers.

Time was like maple syrup, just moving so slowly. I felt like I

was in a totally different world, like everything had stopped, but

I was still going." Swan caught his breath, climbed on

his board and paddled to the beach.

The

attacking White Shark had come from the southwest, between the surfer

and the nearby rocky headland. It had struck the left underside

of the board with its snout, leaving a distinct dent. The shark

then circled around and removed a bite from the right rear of the

surfboard, simultaneously inflicting a single deep laceration to

the surfer's right leg. Upon his reaching shore, Swan's companions

on the beach assisted him to a car and drove him to Mad River Community

Hospital in Arcata. The

attacking White Shark had come from the southwest, between the surfer

and the nearby rocky headland. It had struck the left underside

of the board with its snout, leaving a distinct dent. The shark

then circled around and removed a bite from the right rear of the

surfboard, simultaneously inflicting a single deep laceration to

the surfer's right leg. Upon his reaching shore, Swan's companions

on the beach assisted him to a car and drove him to Mad River Community

Hospital in Arcata.

Upon Swan's admittance to the hospital's emergency room, physician

Preston Smith examined the surfer. Smith cleaned and sutured four

individual tooth punctures. Prescriptions for antibiotics and painkillers

were given to Rodney Swan along with instructions for follow-up

treatment with his family physician. He was expected to make a complete

and uneventful recovery.

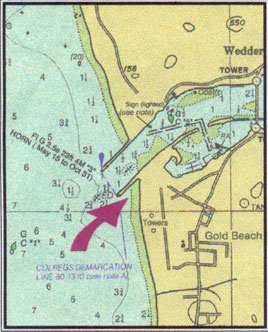

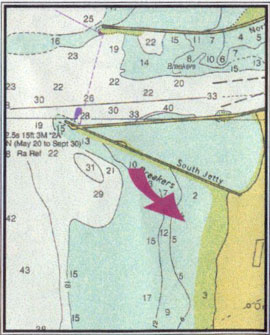

Within

a month of Keith Caruso's attack, surfer Jerad Brittain, age 20, would

be struck by a White Shark. Brittain was attacked on Sunday, 13 September

1992, at 1700 hours, 50 meters from shore, near the jetty at Gold Beach, Curry

County, in far southwestern Oregon (42°25.1'N; 124°25.8'W). Journalists

John Griffith, of The Oregonian in Portland, and Greg Haas, of the Curry

Coastal Pilot in Brookings, generously provided some of the information

for the following incident. Within

a month of Keith Caruso's attack, surfer Jerad Brittain, age 20, would

be struck by a White Shark. Brittain was attacked on Sunday, 13 September

1992, at 1700 hours, 50 meters from shore, near the jetty at Gold Beach, Curry

County, in far southwestern Oregon (42°25.1'N; 124°25.8'W). Journalists

John Griffith, of The Oregonian in Portland, and Greg Haas, of the Curry

Coastal Pilot in Brookings, generously provided some of the information

for the following incident.

Brittain was surfing with his brother, Jeff, about 20 meters from the Gold

Beach South Jetty, adjacent to the mouth of the Rogue River. Brittain

recalled, "I was sitting upright on my surfboard, with my brother

located halfway between me and the jetty. I noticed that all the seals

I had seen just a few minutes earlier were now gone. Then all of a sudden,

while still sitting on my board, I felt this massive jerk on my leash."

The

shark had grabbed the leg leash and began slapping the water with its

tail, striking both the surfer and his board. The attacking shark pulled

Brittain off his board as it headed seaward. The surfer began striking

his assailant with a clenched fist as it pulled him along the surface.

During this struggle, the surfer saw the shark's dorsal fin and tail,

estimating the distance between them to be 2 to 2.5 meters. Within seconds,

the shark's teeth cut the leg leash, allowing Brittain to gulp a breath

of air as he swam toward the beach. He described the shark's color as

dark gray on the back, with a white underbelly. The surfer was fortunate

to receive only several bruises. This was the fourth attack at this

recurring location. The attacking White Shark was 4 to 5 meters in length. The

shark had grabbed the leg leash and began slapping the water with its

tail, striking both the surfer and his board. The attacking shark pulled

Brittain off his board as it headed seaward. The surfer began striking

his assailant with a clenched fist as it pulled him along the surface.

During this struggle, the surfer saw the shark's dorsal fin and tail,

estimating the distance between them to be 2 to 2.5 meters. Within seconds,

the shark's teeth cut the leg leash, allowing Brittain to gulp a breath

of air as he swam toward the beach. He described the shark's color as

dark gray on the back, with a white underbelly. The surfer was fortunate

to receive only several bruises. This was the fourth attack at this

recurring location. The attacking White Shark was 4 to 5 meters in length.

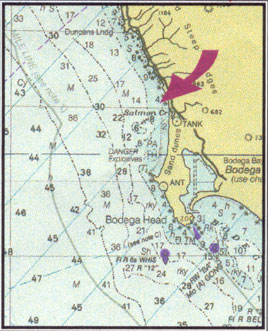

Surfer Kennon Cahill, age 31, was attacked by a 5-m White Shark, on Thursday, 3 October 1996, while surfing at North Salmon Creek Beach, near Bodega Bay, Sonoma County, California (38°21.9'N; 123°04.5'W). He was dressed in a full-body, hooded black neoprene wetsuit with booties and rode a 2-meter white surfboard. The sky was overcast and foggy with the air and water temperature about 12°C. The ocean was "glassy smooth," with a rhythmic groundswell of less than a meter and underwater visibility of 5 to 6 meters. At the attack site the ocean floor is generally sandy, with a few scattered rocks but no dominant kelps. A channel runs from the creek out toward the open sea, then turns parallel to the shoreline for several hundred meters. Surfer Kennon Cahill, age 31, was attacked by a 5-m White Shark, on Thursday, 3 October 1996, while surfing at North Salmon Creek Beach, near Bodega Bay, Sonoma County, California (38°21.9'N; 123°04.5'W). He was dressed in a full-body, hooded black neoprene wetsuit with booties and rode a 2-meter white surfboard. The sky was overcast and foggy with the air and water temperature about 12°C. The ocean was "glassy smooth," with a rhythmic groundswell of less than a meter and underwater visibility of 5 to 6 meters. At the attack site the ocean floor is generally sandy, with a few scattered rocks but no dominant kelps. A channel runs from the creek out toward the open sea, then turns parallel to the shoreline for several hundred meters.

Cahill and his companion, Brendon Guinn, were surfing about 125 to 150 meters from the beach. Relative to Guinn, Cahill was 6 to 10 meters farther out to sea and 15 meters farther north. Guinn checked his watch to confirm that he would not be late for work. It was 0719 hours when Guinn turned to the north to tell Cahill he was heading in. Cahill's board was pointed toward Guinn when he saw, on the shoreward side of his companion's board, a dorsal fin protruding from the water at least 45 centimeters, and only 1 meter from the board. The fin tipped slowly over, away from the board, to an angle of 45 degrees. It appeared to Guinn as though the shark had rolled to better observe Cahill.

Guinn recalled what happened next: "Cahill, as if in a trance, had crouched on his board and was reaching out with his left hand, like he was going to try and grab the shark's fin. It only took a second or two before Cahill drew his arm back in to his chest and let out a loud groan, as his board rocked back and forth. The shark reacted almost immediately by rolling toward Cahill as it came out of the water like a nuclear submarine. Cahill started yelling, 'Shark! Shark!' as the shark thrashed its tail back and forth four or five times, striking the surfboard at least two or three times with its head. Then it appeared that Cahill was trying to ride his board over the shark's back toward the beach. I turned and started paddling toward shore."

While heading in, Guinn turned to his left to try to locate his companion. Cahill suddenly passed him, riding his board all the way through the surf until it ran aground in shallow water. Witnesses on the beach said the shark followed Cahill to within 30 meters of the beach as it repeatedly tried to strike his board. Neither Kennon Cahill nor Brendon Guinn suffered any physical injury, although Park Ranger Michael Wisehart said, "Both surfers were badly shaken by the experience." This was the second attack from this recurring location.

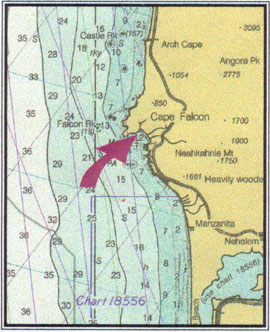

On

Wednesday, 21 September 1994, surfer Rob MacKenzie was attacked by a

White Shark at Short Sand Beach, located in Oswald West State Park between

Arch Cape and Manzanita, near Seaside in far northwestern Oregon (45°45.5'N;

123°58.4'W). He was dressed in a black wetsuit with boots and without

a hood. The ocean was glassy calm with gently rolling 1-meter groundswells

and a temperature of about 14ºC. The water was not very clear,

with visibility of about 2 meters. The ocean floor was 2 fathoms deep, primarily

sandy with a rocky reef at the base of the Basalt Headlands. The sky

was sunny and cloudless, with a light breeze and a temperature of 18ºC.

No pinnipeds were seen at this location. It was about 1630 hours as MacKenzie

sat atop his 2-meter yellow surfboard, 70 meters from the beach. On

Wednesday, 21 September 1994, surfer Rob MacKenzie was attacked by a

White Shark at Short Sand Beach, located in Oswald West State Park between

Arch Cape and Manzanita, near Seaside in far northwestern Oregon (45°45.5'N;

123°58.4'W). He was dressed in a black wetsuit with boots and without

a hood. The ocean was glassy calm with gently rolling 1-meter groundswells

and a temperature of about 14ºC. The water was not very clear,

with visibility of about 2 meters. The ocean floor was 2 fathoms deep, primarily

sandy with a rocky reef at the base of the Basalt Headlands. The sky

was sunny and cloudless, with a light breeze and a temperature of 18ºC.

No pinnipeds were seen at this location. It was about 1630 hours as MacKenzie

sat atop his 2-meter yellow surfboard, 70 meters from the beach.

MacKenzie

and companion Greg Movsesyan had been surfing for about 75 minutes when

they stopped to watch a Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus) breaching

about 1.6 kilometers offshore. About a dozen other surfers were spread out along

the 1.6 kilometer-long beach within the sheltered cove. MacKenzie

and companion Greg Movsesyan had been surfing for about 75 minutes when

they stopped to watch a Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus) breaching

about 1.6 kilometers offshore. About a dozen other surfers were spread out along

the 1.6 kilometer-long beach within the sheltered cove.

Movsesyan reported, "I noticed a gray form passing diagonally

under my board which, because I had surfed often with dolphins in California,

didn't alarm me. The form approached Rob [MacKenzie] less than

15 feet [5 meters] away and, before I could say anything, it surfaced

and bumped the side of Rob's board about three-quarters of the way forward.

Rob went flying into the air, still attached to his board by a seven-foot

[about 2-meters] leash, and came down in the water just in front of the

shark. The board had become impaled sideways on the shark's lower jaw

and, to dislodge it, the shark raised its back half out of the water

and slammed its head on the surface until the board floated free. Then

the shark dived, getting its tail caught on the leash and pulling Rob

and his board under as it swam for deeper water. Under the strain, the

leash broke, shooting the board high in the air and allowing Rob to

surface and retrieve it. We headed for shore, paddling until we reached

waist-deep water. Rob had not been bitten and his wetsuit had only a

graze-mark on the right hamstring, presumably from a shark tooth. We

were both in a state of utter calm, while the beach-goers and the other

surfers were reacting in a great frenzy."

In a letter dated 8 May 2000, Movsesyan described the damage to MacKenzie's

board. According to Movsesyan, an arc of lower-tooth impressions, measuring

35 centimeters across at their widest, punctured the bottom of his companion's

board. The mid-line of the arc, corresponding to the center of the shark's

jaw, was located near the front of the board, about a third of the distance

along its overall length. Movsesyan described the attacking White Shark

as about 5 meters in length. Rob MacKenzie was fortunate to escape without

injury.

|

|

Winchester Bay South

Jetty |

On Tuesday, 24 August 1976, at 1400 hours, surfer Mike Shook, age 19, was

attacked by a White Shark at Winchester Bay in west central Oregon (43

39.8. N; 124 12.8. W). Shook was 100 meters from the beach and 50 meters south

of the jetty in water 1 to 2 fathoms deep. The sky was overcast, with a light

breeze. There was a small groundswell, and water visibility equaled the

depth, as the bottom could be seen clearly from the surface. Shook had

been surfing about 45 minutes and had not observed any pinnipeds near

him.

Shook was lying on his board attempting to catch a

wave when he felt a slight bump to the rear of the board. This was

quickly followed by a more forceful jolt, which caused the surfer to

glance back. Much to his surprise, a large White Shark had the rear of his

surfboard in its mouth. The shark swam along the surface, pushing the

board and rider 5 to 10 meters before the end of the board broke off in the

shark's mouth. The shark released the piece of board it had broken off,

then submerged out of sight. Shook swam toward the jetty with the broken

end of his board attached to his ankle leash. The White Shark was

estimated at 4 to 5 meters in length. Shook was not injured.

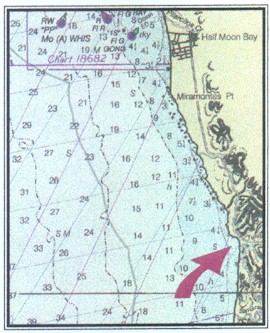

On

Saturday, 15 August 1987, Craig Rogers, age 40, was attacked by a White

Shark while surfing off Tunitas Creek, near Half Moon Bay, San Mateo

County, California (37°21.6' N; 122°24.5' W). His surfboard was 2.1

meters in length, square-tailed, and colored white with numerous decals.

It was 0730 hours, with an overcast sky and an air temperature of 18°C.

He was 200 meters from shore in murky water 3 to 4 fathoms deep, with visibility

of 1 meter and a temperature of about 15°C. The ocean floor was sandy, and

there were no marine mammals observed in the area before or following

the incident. On

Saturday, 15 August 1987, Craig Rogers, age 40, was attacked by a White

Shark while surfing off Tunitas Creek, near Half Moon Bay, San Mateo

County, California (37°21.6' N; 122°24.5' W). His surfboard was 2.1

meters in length, square-tailed, and colored white with numerous decals.

It was 0730 hours, with an overcast sky and an air temperature of 18°C.

He was 200 meters from shore in murky water 3 to 4 fathoms deep, with visibility

of 1 meter and a temperature of about 15°C. The ocean floor was sandy, and

there were no marine mammals observed in the area before or following

the incident.

Rogers had been surfing only five minutes and

was sitting on his board, legs dangling off either side. His hands

were on each rail just in front of his legs as he gazed appreciatively

out toward the horizon. Rogers' surfing companion, Tim Burraston,

was 200 meters south of him. Rogers had been perched on his slowly

rolling surfboard for several minutes when he noticed that his board

had suddenly, but almost imperceptibly, stopped moving in the water.

Without moving his head, he lowered his eyes, coming to focus on

the head and eye of a "huge" shark. The shark had gently

grasped the surfboard, just millimeters in front of his left hand.

Rogers thought he and the shark remained frozen, almost motionless,

for several seconds. They both seemed to release their respective

grips simultaneously, with the little and ring fingers of Rogers'

left hand striking the protruding teeth of the shark's upper jaw.

After releasing his grip, Rogers slid off the

right rear of his board and grabbed its edge with both hands. With

only his head protruding above the water, he watched as the shark

held the board firmly in its mouth for several seconds before finally

releasing its hold and submerging. As soon as the shark relinquished

its grip, the surfer climbed back on his board. As water swirled

all around him, Rogers watched the shark submerge and swim beneath

his board. Straining to be heard above the roaring surf, he yelled

to his friend that a shark had attacked him. It was several seconds

before Burraston realized what had happened. Rogers caught a wave

and held on until his board "bottomed out" in the surf.

|

|

| Rogers and his companion drove to Emerge-Care Medical

Clinic in Santa Cruz. Dr. Stanley Hajduk treated the surfer's wounds,

which required seven sutures. The wounds were cleaned and dressed and

antibiotics were prescribed. According to his physician, the surfer

was expected to regain complete control of his fingers and hand

without any permanent impairment. |

|

|

|

|

During its gentle contact with Rogers' surfboard, the shark left its

"calling card" in the form of two whole teeth. In addition,

the impressions left by the shark's teeth were easily identifiable

by their spacing. This permitted a reliable size estimate for

the attacking White Shark at 5.7 meters in length. The surfboard,

with accompanying White Shark teeth, is currently in a surfing

museum in Santa Cruz. |

If you, or someone you know, has been involved in a shark attack and would

like to voluntarily participate in the Shark Research Committee's research

program, please use the appropriate reporting form.

|